Plague stones, Bronze Age bog mummies, haunted trees, ancient burial mounds—in James Brogden’s England, the ancient dead won’t stay buried and the ley lines are always buzzing with dread. By why take my word for it? In The Veil interview, Brogden neatly sums Britain’s violent post-Ice Age history: “For thousands of years different cultures have settled and made this island their home, often violently, and as a result the British landscape is a palimpsest of blood and beliefs.”

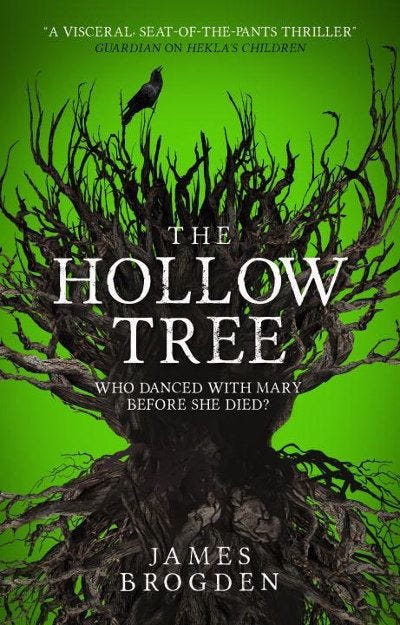

Not the stuff of tourist pamphlets, for sure, but that view is far more intriguing—and accurate—than the one peddled by the creators of Downton Abbey and The Crown, where it’s always tea time and the servants are happy in their place. Through a series of novels that blend folklore, history, fantasy and gut-munching horror, Brogden has created an alternative England as magical and haunting as the best imaginary lands of fantasy fiction. Hekla’s Children is as good a place as any to begin your journey: there’s a plague demon, missing children, an ancient warrior named Bark Foot and a lot of cannibalism. The Hallow Tree is in more of a Gothic vein, while The Plague Stones reads a bit like a classic British YA mystery with all the violent bits left in. You can’t go wrong, really.

Brogden’s refusal to be boxed inside any one (or two or three) genres may have something to do with his somewhat peripatetic childhood. He describes himself as a “part-time Australian who grew up in Tasmania and the Cumbrian Borders, who has since escaped to suburbia and now lives in the Midlands, where he teaches English. When not writing or teaching he can usually be found up a hill, poking around stone circles and burial mounds. He also owns more lego than is strictly necessary.”

The Veil: What got you hooked on horror when you were young?

James Brogden: Getting introduced to the work of James Herbert at the age of fifteen. I’d been reading science fiction and fantasy pretty solidly up until then, and my family moved to England where I met my adult cousins for the first time since I was a baby. One of them loaned me his copy of The Rats and I devoured everything of Herbert’s that I could, and that led on to Clive Barker, and everything followed on from there.

The Veil: Your work is steeped in folklore, landscape, mythology, history and horror. Were you drawn to those images and stories at a young age or did you come to them later?

JB: If you’re talking about the kinds of things young children read—or have read to them, if their parents are doing their job right—like nursery rhymes and fairy tales, well those things have folklore and mythology as their DNA. When you move on to “classic” children’s literature you’ve got Alice in Wonderland, the riverscape of The Wind in the Willows, Middle Earth, Narnia, even the Famous Five with their adventures on moorlands and islands. I don’t see how you can “come to them later”; if you’re literate to any degree you’ve already been immersed in them, just without realising.

The Veil: When did you realize that you wanted to be an author?

JB: I’ve always written stories, and I’ve always wanted people to read them because I’m a big narcissist, so I couldn’t put that down to a specific lightbulb moment. I’d buy horror magazines like Skeleton Crew and read the stories in them and think, “Hey, that’s the kind of thing I write, I wonder if they’ll print mine?” Then I’d send my stories off because what was the worst that could happen? And so I got some small successes and thought, Right, let’s try something longer, and I had a crack at a novel, which only took, you know, twenty years to get published…

The Veil: You’re also a full-time English teacher. How do you find the time to write at such a prolific rate?

JB: I don’t know about prolific. A novel every year or so feels pretty slow to me, but yes, it’s all about the balancing act with the Day Job. I tend to plot and scheme during term time, because that’s really all I have the time and the brain power to do, maybe write a few hundred words a day if I’m lucky, usually in a notebook. Then the holidays roll around and I very generously give myself the first weekend off and it’s get typing the first Monday morning of the break. Summers are writing time. I’m very lucky and privileged in that sense; I have huge respect for those writers who are also working a Day Job which doesn’t have that kind of perk. At the same time, I’m too much of a coward to take the plunge and go all-in with the writing.

JG: Your earlier novels could just as easily be described as fantasy and your work also incorporates tropes from historical fiction, mysteries and the police procedural. I’m curious about how the traditional elements of the horror story came to dominate your work. Is there a point in the writing process when the storytelling techniques of the police procedural or fantasy novel are subordinated to the tale of terror, or do you know from the start what you’re writing?

JB: Without wanting to sound facetious, the traditional elements of a horror story get foregrounded when an editor tells me that’s what they’re after. I’ve always thought of what I write as a form of fantasy—I mean the first three novels that were published by Snowbooks were about ley lines, lucid-dreaming-assassins and alternate steampunk worlds. When I wrote Hekla’s Children I was throwing in all kinds of things that pushed my buttons, and I was very surprised when the editor told me that it was going to be marketed as Literary Horror, because in all honesty I thought I was writing Robert Holdstock fanfic. So then that led on to three more books with Titan, by which time they were marketing me as horror. That expectation influenced the kinds of ideas I came up with. The Plague Stones was the first time I sat down to self-consciously write a “horror” story with actual tropes and things. If you’ve got a story where people are being killed in gruesome ways that police are going to get involved at some point, but that’s not a police-procedural trope, it’s just narrative logic. The story that I’ve just finished writing isn’t for a contract or commission, so I’ve been able to go off piste a little more and it feels like a gothic fantasy, but who knows?

The Veil: Since the publication of Hekla’s Children you’re apt to be described as a writer of folk horror. Are you comfortable with that descriptor?

JB: Only insofar as it helps them to get a handle on what kind of story they might be expecting. I don’t have a huge amount of time for people who get annoyed and write negative reviews about, Oh this wasn’t a proper folk horror novel, it was more of a fantasy, because I’m like, Mate, be a bit more flexible with your expectations, you know? Genre is a menu—use it to pick something you like the taste of, but expect the chef to use ingredients you might not be expecting. Unless what you’re after is MacDonalds. In the end, it’s a marketing thing. It’s a fashionable genre label at the moment and eventually it’ll get replaced with something like “rural unease” or “grim-hedge.” If someone says to me, I want you to write a thing with scythes, I’ll put scythes in it because I’m a jobbing writer and someone’s paying me.

The Veil: How would you describe folk horror? What elements need to be in place for a work to be considered folk horror?

JB: I don’t really know. I’ve read novels that have been recommended to me as classic folk horror and I think, That’s a cracking ghost story or That’s weird lit-fic, I like it, but tropes like haunted indian burial grounds and demons in the the corn have been used for ages without this particular label, so it’s not as if folk horror is especially new.

This is going to get political—sorry in advance.

I’m not a big fan of the term and it’s not something I set out to write. Locating evil or danger in “folk” culture becomes problematic when you start to unpack it as taking predominantly rural and working class traditions, stories, customs etc. and making them the source of a threat. Take witches, as a classic example. There’s a general consensus that, historically speaking, witch hunts were misogynistic crimes of appalling brutality committed against some of the most vulnerable and powerless people in society. And yet there’s plenty of folk horror still using the evil witch figure (usually in films, it has to be said) without any apparent awareness. It’s a short jump to take local beliefs and customs and paint them as superstitions, and to “other” those that observe them as ignorant peasants at best, or active cultists at worse—especially if your protagonist comes from a privileged and educated background. What we often forget in Britain is that our “green and pleasant land” is the historical product of an aristocratic power elite enclosing the common land and demonizing and exploiting its inhabitants for generations, so I’m a bit wary of stories which reinforce that by writing about mobs of pitchfork-waving peasants worshipping the Thing That Lives in the Barn, if you know what I mean.

The Veil: Why is landscape and a sense of place so central to folk horror (in general) and your work (in particular)? Why does the landscape of the UK seem to generate so much “place-based” horror and folklore?

JB: Well for a start it’s so bloody OLD, isn’t it? You’ve got human habitation going back to Paleolithic times with monuments older than the Pyramids, so that’s a wealth of story material right there. For thousands of years different cultures have settled and made this island their home, often violently, and as a result the British landscape is a palimpsest of blood and beliefs. And also with regard to my previous point: it’s a landscape of secrets. Less than one tenth of the countryside is open for public access—the rest is fenced off by wealthy families, corporations and the Crown. You have to wonder what they’re hiding. It’s not the villagers that you want to be afraid of, it’s the lord of the manor, locked away behind his huge gates, performing forbidden rituals in ancient groves.

The Veil: A lot of contemporary folk horror relies on a half-glimpsed but terrifying suggestion of a distant past that still holds sway over a particular place and/or group of people. Your work is very different in that you give readers a detailed, historian’s view of the real and mythical past. What draws you to these rich (and often horrifying) recreations of prehistoric and more recent historical eras and the folklore they’ve spawned?

JB: I’m very much of a “show the monster” kind of writer. Yes, the build-up, the mystery, the terrifying suggestions are all important parts of the narrative, but I like the reveal a bit more straight up and in your face. So for example, in Bone Harvest the cult and the god that they worship are shown in the first few chapters rather than being revealed towards the end because let’s face it, the reader has a pretty decent idea of what’s coming, don’t they? What’s interesting to me is not so much, What is the monster? but, Okay, here’s the monster, now how do people cope with it? In the case of folk horror, history can be the monster.

The Veil: Although depictions of violence are not central to your work, you don’t shy away from the blood and guts. What role do you think violence and gore plays in the best horror fiction?

JB: Horror is, at its heart, about fear, and there is no more basic or visceral fear than that of bodily harm. I’ll use it because it’s part of the toolbox—when and how, well that’s the craft isn’t it? Splatterpunk has a noble place in the genre, and I like a bit of gonzo blood and gore now and then. Midnight Meat Train is fun.

The Veil: What are your favourite horror novels/stories?

JB: So many, and genuinely no idea where to begin. It’s usually what I’m reading at the time, which in this case happens to be The Roo by Alan Baxter—one of those gleefully gonzo blood and guts stories I was talking about earlier. I went on an MRJames bender and reread Weaveworld again recently, but I’m not sure how many people would say those are horror. That genre thing again.

The Veil: What are your favourite horror films?

JB: Again, this is a lot harder to answer than you might think. Near Dark is the first thing that springs to mind. Razorback because The Roo reminded me of it. Aliens, obviously. Anything and everything by John Carpenter. I’m an 80s kid.

The Veil: One last question. Do you have any recommendations for readers, especially recent films or books that they may not have heard about?

JB: The Last House on Needless Street by Catriona Ward.

The Veil: I’ll second that reco, thanks.