Books have been written and documentaries released about the intersection of countercultural politics and DIY filmmaking that fuelled the explosion of groundbreaking horror films in the late 1960s and 1970s. In these studies and testimonials, the war in Viet Nam, the student protests at home, and the Civil Rights movements are rightly listed as disruptive forces that unleashed the imaginations of a generation of young radical artists who wanted to expose America’s crimes and hypocrisies to the world. In doing so, they created what we now know as the modern horror film.

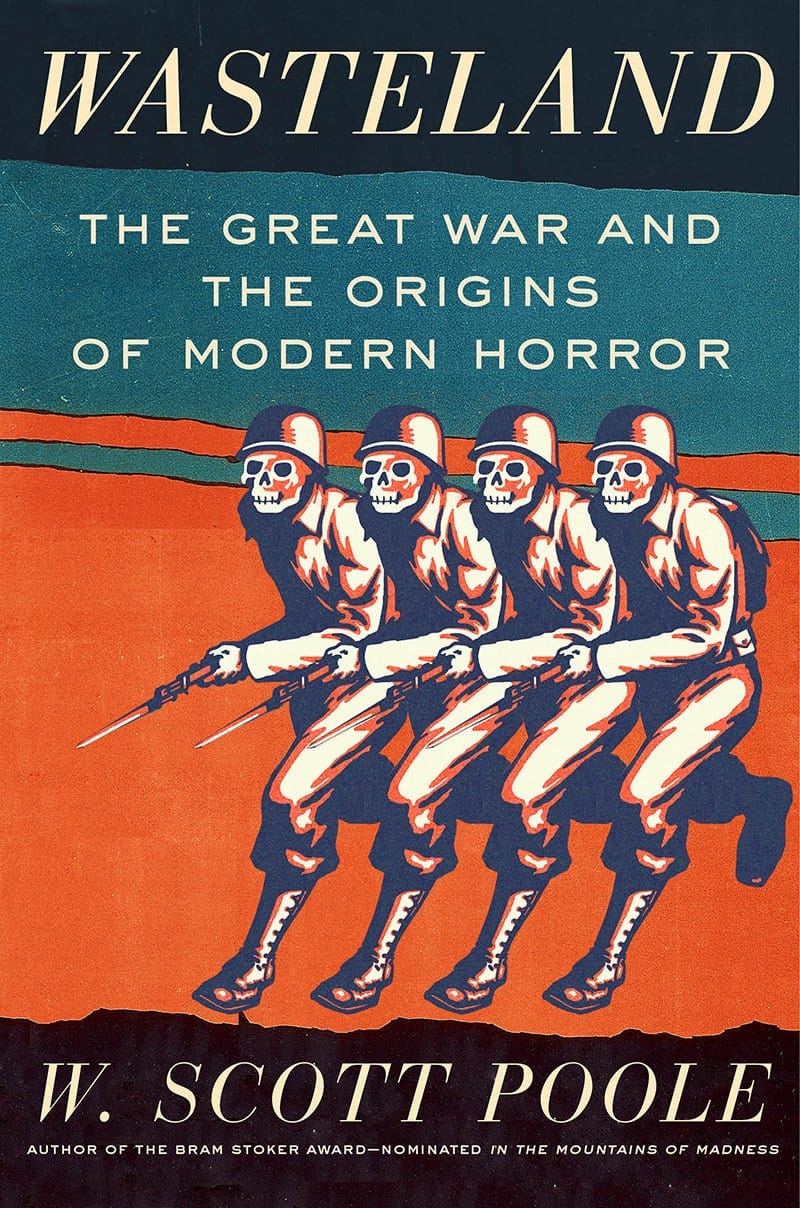

So the story goes. Less has been said and written about the influence of World War One on the first wave of directors, screenwriters, actors and artists who created the iconic horror films of the 1920s and 1930s. With his painstakingly researched but lively and reader-friendly study Wasteland: The Great War and the Origins of Modern Horror, historian, academic and horror nut W Scott Poole restored The Great War to its rightful place as the Mount Doom of modern horror. As Poole revealed, the list of traumatized veterans in the Horror Cinema Hall of Fame is striking. Directors and screenwriters F.W. Murnau and Albin Grau (Nosferatu), Fritz Lang (Metropolis, M), James Whale (Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein), Abel Gance (J’accuse), and Paul Wegener (The Golem) all served at the front, while Bela Lugosi, for many horror fans the only Count Dracula, was a decorated veteran of the Austro-Hungarian army. All witnessed the mashing of millions of bodies to a pulp and recombined into grotesque shapes, an experience we still see acted out in the zombie films and works of body horror.

W Scott Poole spoke to The Veil from his home in Charleston, South Carolina, where he teaches in the History department at the College of Charleston. He is also the author of Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror, In the Mountains of Madness: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of H.P. Lovecraft, and Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting.

The Veil: How did you get into horror?

W Scott Poole: I was a young kid. In fact, I don’t recall a time when I wasn’t a horror fan. For me it really has been a lifelong passion. My introduction was two-fold. First was Saturday afternoons, with our local TV station’s version of Shock Theatre—which did not have a horror host! That’s something I totally missed out on, which is part of the reason I’ve been obsessed with horror hosts ever since. I would sit down every Saturday afternoon from age four until about ten and just watch everything from junk—like Attack of the 50-Foot Woman—to Dracula, Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, etc.

Then, with great deceit and subterfuge on my part, I managed to convince my mom, who was kind of checked out on popular culture at the time, that Stephen King was perfectly appropriate reading for a ten-year-old. I was reading The Stand and Carrie and Salem’s Lot before I was a teenager. Now I did eventually get caught! I’m still mad and still searching for the Bookmobile lady who told my mother that King was not appropriate reading material or whatever.

The Veil: Yes, my mother let me read whatever I wanted, within limits, so long as it didn’t have any scenes of demonic possession. It was a Catholic thing. My father had a copy of The Exorcist, but once my mother realized I was getting into horror that book disappeared from the shelves.

W Scott Poole: The irony there is that The Exorcist is one of the most Catholic books ever written!

The Veil: Yes, but she hadn’t read it. My father did, but that was okay because he was Protestant! So how did your love for horror merge with your love of history?

W Scott Poole: That happened in school. I was an English major that did a Masters in Anthropology and Religious Studies and a PhD in American History. I was lucky enough to get a sinecure in American academia at a time when you could study whatever you wanted and not get fired. So I asked myself what I really cared about? One thing I cared about a lot was how politics and cultural history go together. Then I discovered, by looking at the materials that interested me, that those two things had intertwined in sometimes cool, sometimes really unsettling ways.

The Veil: Do you think that’s especially true because you’re from the American South?

W Scott Poole: No. And there’s a reason I’m so sure about that. Consider the quote from Malcom X: “When you’re talking about the United States, south is south of Canada.” Racism may look differently in New York City than it does in Charleston, South Carolina or Birmingham, Alabama, it’s structural power is the same. My parents were moderate liberal Democrats, so some of the stuff that I heard outside of the house that was really nasty and racist, that like any kid I’d thought, That’s just how it is, well, my parents would correct when I brought that stuff home. They told me that some words were not okay and there was nothing cool about the Confederate flag. We had a big controversy in my household about The Dukes of Hazzard, because of the General Lee car and the Confederate flag.

So yes, there was something about being in the American South, where the culture and language has been so openly racist, that made me interested in how that all tied in with the surrounding culture. But structural racism is a deeply American problem, and the South has played the role of the country’s cultural garbage can. It allows other Americans to say, “At least we don’t say those words with that accent.” Sure, we redline neighbourhoods and we build highways that cut off neighbourhoods where Blacks and Latinx—and a lot of working-class whites—live, so that they can’t get to the rest of the city, but it’s not like the South. That’s the theme of Candyman, which is about Chicago.

The Veil: We have a similar dynamic up here in Canada, where we say, “Sure, we have racism, but at least it’s not American racism.” White Canadians can pride themselves on perhaps being more “publicly” sympathetic to the plight of racialized communities, but sympathy will only take you so far.

W Scott Poole: That’s absolutely true. One of the things that really hit me in my studies was thinking about the movie audiences who saw James Whale’s Frankenstein when it came out in 1931. This was the during dead centre of a historical period that African Americans refer to as the “nadir,” which includes not only the time of official segregation in the South—and de facto in most of the rest of the country—but also the period of very public lynchings. Between 1888 and 1948, there were five thousand African American men murdered in these very public spectacles. This was not the Klan or the rednecks lynching Black men in the woods in the middle of the night, but out in the open in small towns across America.

Watching Frankenstein as an adult, I was able to sympathize with the Monster. And maybe audiences in the Thirties did, too. But there would have been people sitting in that audience who had been the villagers with the torches and pitchforks chasing the Other into the hills for a crime against a white child. There would have also been people in the audience who felt sympathy for the Monster but said to themselves, “Well, he did kill that kid… It’s sad, but it has to be done.” When you think about how much vocal support there was for the violence against the Black community in those years, the film takes on a very different meaning. Thinking about how actual horrors had intertwined with horror fictions in that film, and how different audiences would read it at different moments in history—that was very interesting and disturbing to me.

By the way, there is some evidence that James Whale understood that dynamic. He had become friends with Paul Robeson, who he later worked with on Showboat, so he would have been aware of what was happening. He also framed some of those moments in the film to mimic D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. The shot in Frankenstein where the father is carrying Maria into the town and saying, “A monster did this to my child, let’s go get him,” that replicates a very sinister scene from Birth of a Nation.

The Veil: And the “storming of the castle” scene is not even in the novel.

W Scott Poole: Yes, it’s one of the very Americanized scenes added to a British story. And speaking of the British, there was a British review of Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein—which also had a scene with villagers and torches—which said that the second half of the movie reminds the viewer of “nothing so much as a Georgia lynching.” So people outside of the American Imaginary immediately saw what was being staged and restaged and how audiences would have been reading that.

The Veil: Given your interest in horror, history, and cultural history, do you think it was inevitable to write about the First World War, as you did in Wasteland? So many creators of early horror cinema were veterans of that war.

W Scott Poole: Absolutely. I’m obviously not the first person to make the connection between horror and the First World War. David Skal, an amazing writer and person, noted that connection in his book The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, but he couldn’t go into it in too much detail. But as I wrote my book, I realized that the connections between the First World War and horror were far deeper than I’d imagined. There had been some academic work on what James Whale, who was a veteran, might have brought to Frankenstein and The Old Dark House and The Invisible Man, but I didn’t expect to find this entire network of writers, artists and filmmakers—often the same people, because the dividing line between art and film was not yet established—all of them had had horrific experiences in the war.

I did feel a little out of my depth when I began Wasteland because I was an American scholar writing about a primarily European conflict and European cultures. It was revealing to me as an American historian to grapple with the impact of that war outside of the States. Because we didn’t enter the war in a serious way until 1918, Americans don’t really know about the Great War. For us, it’s a precursor to World War II. That makes sense because compared to other nations, our losses and involvement were fairly negligible. But because I knew I’d be writing for a mostly American readership, I had to better understand the overall impact and also think about how an American would read my work. For instance, they probably wouldn’t know that Europeans experienced the First and Second World Wars as a kind of single historical period. We didn’t.

The Veil: I keep coming back to an idea you explore in the book, that the Great War “shattered the Victorian consensus about death.” It wasn’t only the sheer scale of death in the war but the manner of death, how the bodies were literally disintegrated by the new machines of war. The veterans were traumatized, and so were the people at home, who were not able to mourn over the physical remains of their loved ones. The ornate Victorian funerary rites of the time were impossible without a body. How do you see that and other traumas showing up in early horror films?

W Scott Poole: There had probably never been a previous moment in history in which human beings had encountered—and lived with—so many corpses. That was the nature of trench warfare: you’re sort of stuck there with the bodies. The American Civil War and the Napoleonic War produce a lot of corpses, too, but nothing like the number of the Great War. And in those wars, you broke camp after the battle and moved on. You didn’t live them in the way World War One veterans did.

That comes up not only with the fascination with dismemberment—especially in Frankenstein—but with the fascination in early European horror films with the doppelganger and doubles in general. Yes, you can go back to ETA Hoffmann and Nathaniel Hawthorne and find themes of the Fear of the Double and the Fear of the Mirror. But the inflexion given to the Double by war veterans is that these bodies are not necessarily the resurrected dead or the dead self—the Double or the reflection in the mirror actually reveals that your body is not a special creation made by God but a mechanism that can be torn apart. Any animated or reflected version of that body is therefore a kind of curse. This is the opposite of older Christian notions of eschatological rebirth and new life. It’s not a new life, it’s un-death. It’s not surprising then that French director Abel Gance gives us the first zombie film—in the way we think about them, as a reanimated army of the dead—in J’accuse.

The Veil: You can also read the doppelganger image psychologically, in that the notion of the self has been shattered along with all the bodies. Your former vision of your integrated self is now both “You” and “Other” because you no longer really recognize yourself.

W Scott Poole: Exactly. I became fascinated with exploring those ideas outside of horror cinema. On the stage in Germany you see these various plots centred around the veteran who is supposed to be dead or thought to be dead. So his wife moves on and remarries, but he returns alive and it’s not a happy homecoming. In the work of playwrights like Brecht, it ends in double homicide-suicide and horrific violence. That’s an also an aspect of the disintegration of these elaborate funerary rites not only for Victorian England, but for all the European empires. These rites were not only religious, they had to do with notions of respectability, of catharsis and of moving onto a new stage in life. World War One just destroys this.

The Veil: Do you see the horror genre in general as—at least in part—a means of dealing with periods of collective upheaval and trauma? Horror always seems to make a comeback during periods of violent change, with the First World War being a particularly graphic example. So the Gothic becomes a dominant genre in British literature for much of the nineteenth century as traditional British culture is repeatedly attacked by the forces of industrialism, radical political ideas, Darwinism, etc. We’ve had monsters and folklore for millennia, sure, but have the particular traumas and upheavals of Modernity provided the impetus for modern horror?

W Scott Poole: I’m glad you asked about that because one of things that really pissed me off about some reviews of Wasteland is the suggestion that I was somehow unaware that there were stories of the supernatural before the Great War! As you know, what I was trying to say is that, what we think of as modern horror is weaponized in a very specific way by the war, not that all of a sudden people became interested in supernatural monsters.

To your point, it is very important to consider the genealogy. We can look at different turning points in Modernity, going as far back as the 16th century, when you have up to 50,000 people executed for being witches. The belief in Satanic pacts with the Devil that led to those deaths happened at the same time as the beginning of the Scientific Revolution and the rise of capitalism in Europe. The French Revolution also connects with Gothic fiction. The Marquis de Sade, who probably shouldn’t be brought in as an authority on too many things, said the Gothic was necessary because the French Revolution had ginned up the nervous system of everyone in Europe. They were all so anxious about the fall-out that literature had to respond to a world that was scary and exciting and anxiety-producing.

The Veil: In some ways, H.P. Lovecraft, about whom you’ve written extensively, was also responding to the very modern trauma of atheism. He tried to style himself as this supreme rationalist, and yet his work is all about the terrors of an impersonal universe. Do you see him as an exemplar of this “Fear of Modernity” thesis we’re getting into here?

W Scott Poole: Absolutely, in part because he reflects all the fault lines and contradictions that go along with Modernity. He’s an atheist who in so many ways wants the world to return to a traditional 18th-century notion of how an ideal society should work. He’s in a rage against Modernity. At the same time, he talks about one of the pillars of that older society he idolizes—Christianity—like Nietzsche does, with total disdain. That’s where Lovecraft got most of what he said about Christianity.

Part of what comes out of that worldview is a kind of secular ideology of doom. It has the very conservative element of looking back to a perceived paradise. For today’s conservatives, that might be the 1950s. For Lovecraft, it was Georgian England. But in that process of looking back there is always a sense of loss, that we have gone from an organic society to a mechanical society and we can never get it back. So like the unfortunate protagonists of most of Lovecraft’s stories, the “very flowers of springtime are now poison to me” as the narrator puts it after he discovers that Cthulhu is the real power behind the universe. I think that’s why there’s so much more fascination with him now than in his own lifetime: Lovecraft is, in many respects, including in his nativisim and racism, very much a figure of our own moment than of that time.

The Veil: It is interesting that this reactionary figure is so beloved by the contemporary horror community, which very much sees itself as politically progressive. Fans are wont to argue that horror is transgressive and progressive, which it often is, but we can’t ignore the genre’s deeper appeal to the irrational in us. The engine of any work of horror, no matter how subtle or progressive, is terror and pity and sex and violence.

W Scott Poole: I read a book recently that shed a lot of light on that idea for me, because I agree with you about the how irrationality that gets unleashed is part of the whole culture of excess in horror. The book is Maggie Nelson’s The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning. In it she touches on horror films and questions the claim, made by many defenders of horror films, that horror works as a form of Aristotelean catharsis. If that’s true, she suggests, then all that pity and terror aren’t being purged because people keep coming back for more and more. But one of the overall points of her book is that refusing to look directly at cruelty is also wrong. We horror fans hear that all the time; people say, “I don’t want to expose myself to what’s on the screen,” that they might not be able to forget what they saw. I find that fascinating because it’s the same kind of mentality that many of us bring to learning about what’s happening in Yemen or Syria. We say, “It does me no good to look at that cruelty,” so we don’t look.

Horror, in spite of its Bad Boy reputation, is actually home to some of our best and most progressive directors. They realize that when you look directly at irrationality and even open the door to it, that violence can go a lot of different ways. We make choices. Violence is also very much celebrated in Fascism, and some horror does share that glorification of violence. But the best horror sees something good in our refusal to look away from cruelty. Susan Sontag explored that in her last book, Regarding the Pain of Others, where she says that we may think of watching as sensationalistic or exploitative—and it can be—but there are some forms of pain in the world that are so terrible that the only thing you can do to make yourself a real human being is to witness them. There is horror that punches us in the face, and instead of turning us into serial killers, encourages a tendency toward empathy. And I’ve seen that very much in the horror fan community. In real life we have empathy.

The Veil: One last question. What monsters do you see emerging right now (and in the near future) to help us negotiate the horrors of our time? Anyone due for a comeback?

W Scott Poole: I think the monsters on the horizon are tied into what I think will be the major geopolitical conflict and simultaneously the major ethical question of the 21st century: online digital life and, concomitantly, artificial intelligence. Both can be, and are being, weaponized. In both I think we find various threats to democracy and to our own identity. We’re already seeing a number of “online” horror films, Zoom being the best. Ex Machina is also a preview of what’s likely to be a debate within a very few years—if we disregard some of the creators of AI and make it “human-like,” doesn’t that raise questions about autonomy, personhood and the meaning of exploitation. In the real world, the race does seem to be about making soldiers and sex workers and both are terrifying prospects in different ways.