Send Out the Clowns

A few thoughts on the inherent creepiness of clowns, fortified by a gruesome childhood anecdote

When my brother and I were kids we used to scour the TV guide for news of the next The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast, a program that appeared irregularly on NBC for several years in the 1970s. For those who missed out, Las Vegas legend Dean Martin would gather together a handful of his Hollywood buddies into the MGM Grand Hotel’s Ziegfeld Room, where they turned their comedic talents on the evening’s roastee, usually a fellow celebrity.

Never mind that we didn’t always get the jokes: for one golden hour, we got to watch the stars of our parents’ generation—Milton Berle, Lucille Ball, Red Skelton, Don Rickles—act like kids at a sugar-fueled birthday party. They backslapped, they pounded the banquet tables, they chugged highballs and wiped tears from their flushed cheeks as schoolyard insults rained down on the chosen victim, who got to fire back at his or her tormentors to close out the show. At home, we guffawed and chugged our Cokes like a pair of high-rollers waiting for our turn at the podium.

What we didn’t know was that Dean and his buddies were updating, for our wised-up TV sensibilities, a very traditional comic figure: the clown. No, they weren’t wearing grease paint, polka-dotted onesies and rubber noses, but for the duration of the comedic bacchanal, these modern-day clowns were given license to ridicule social hierarchies, call out hypocrisy and corruption, and act out the anti-social impulses kept in check by convention. The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast called out the “phoniness” of the entertainment business, but when the show was over, the guests who’d let down their masks for an hour would be back shilling their latest projects on the talk-show rounds the next day with gushing enthusiasm.1

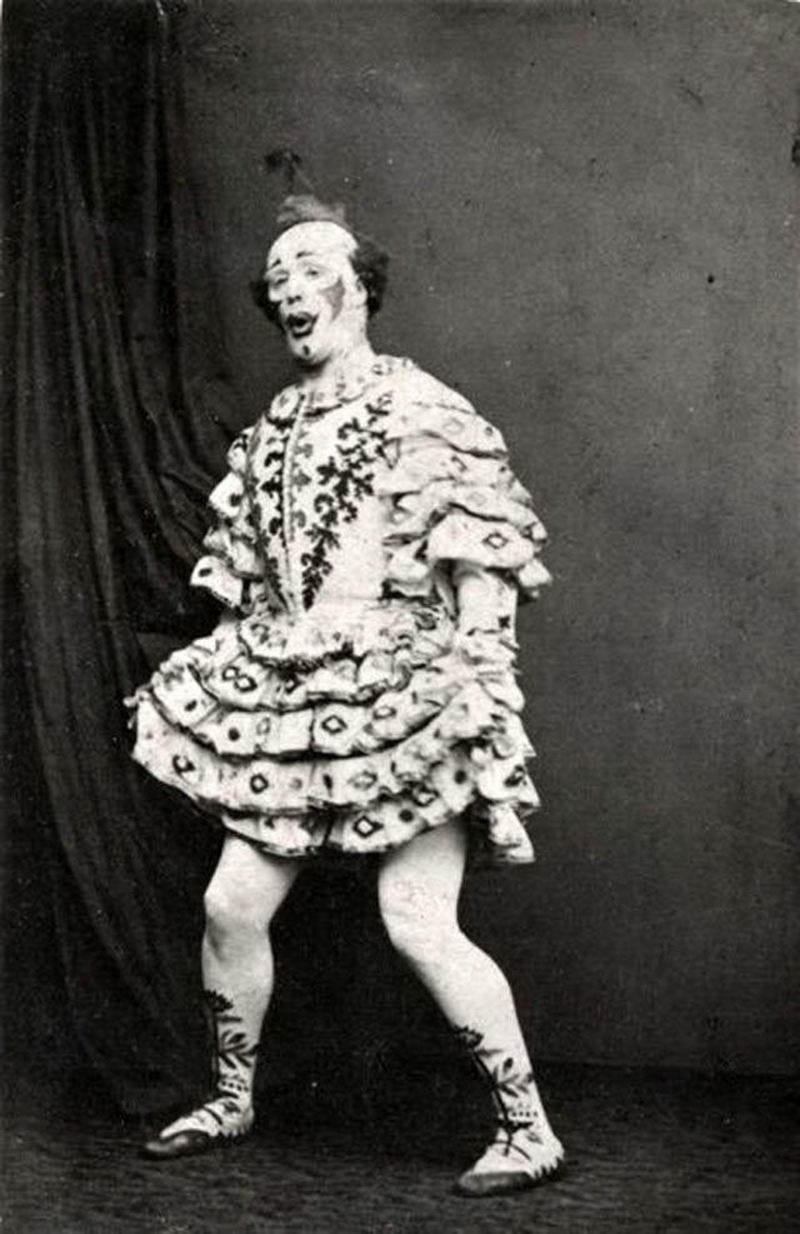

The fright-wig-and-silly-shoes circus clowns that stalked local TV kids’ shows like Romper Room and The Uncle Bobby Show simply could not compete with Don Rickles calling Frank Sinatra a “hockey puck.” It wasn’t so much that we 1970s kids were devotees of the New—me and my friends loved The Three Stooges and The Little Rascals—but having grown up with relaxed, post-1960s social mores, we didn’t know what those old-school clowns were making fun of. The circus itself, the natural arena of the clown, was also a relic of a pre-TV era when you had to get dressed up and leave your house to be entertained.

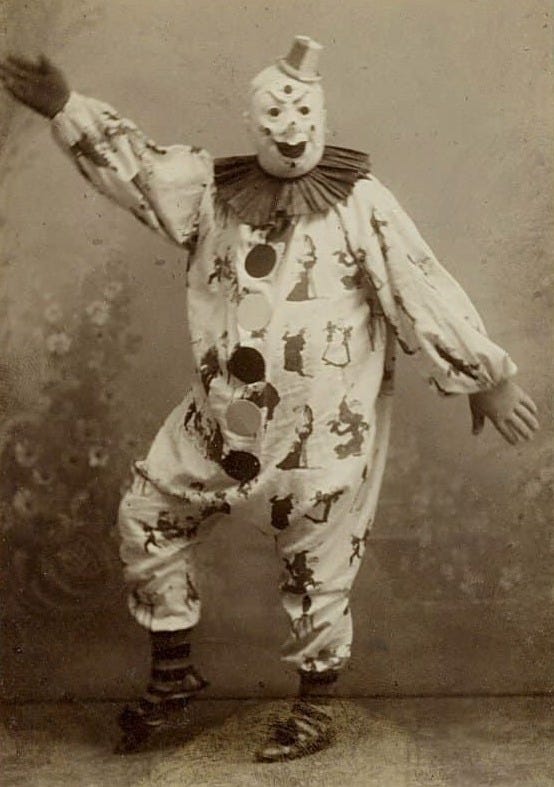

So, no, we didn’t think traditional clowns were funny. But scary? Oh, yeah. Terrifying. Why clowns are scary is the subject of much speculation. One theory goes that clowns scare us because we can’t read their true facial expressions beneath the makeup, which, coupled with their unpredictable behaviours, triggers a danger signal deep in our brains. Clowns can also trigger the same feeling of uncanniness as dolls and mannequins, a sense that they are neither truly alive nor truly inanimate. All of these theories point to a crisis of interpretation.

An even more unsettling thought: if clowns are permitted to act out anti-social and libidinal impulses on stage, under the watch of authority figures, imagine what taboos they violate when no one is around. From a child’s point of view, it’s one thing for a six-foot-plus stranger to come in and act naughty for 20 minutes at your crowded birthday party, but would you want to be alone with the guy? Would you want him to babysit you?

Which brings me to perhaps the most grotesque of my childhood anecdotes, an incident of such surreal violence that only a few years back I had to ask my brother: Did it really happen, the thing with the clown?

He assured me it had happened, and that it was as awful as I remembered.

This was some time around 1975. My father, whose job as a bartender at a hotel tavern (and his never-fully-explained connections to the criminal underworld) gave him access to free tickets to concerts and sporting events, nabbed us lower-bowl seats to a big American circus that came to town. My brother and I would have preferred hockey tickets, but the circus was at Maple Leaf Gardens, one of the three shrines of my childhood (along with the Royal York Hotel, where my father worked until 1973, and the Royal Ontario Museum). Walking the Gardens’ crowded corridors, I took in, through a cloud of cigarette smoke as thick as cotton candy, the familiar photos on the walls, a pantheon of toothless hockey players, the heroes of my uncles’ childhood, baptized in champagne by old men in fedoras in the Maple Leafs dressing room. There were also prize fighters whose bright eyes were encased in swollen flesh and wrestlers in Speedo prototypes flying from the turnbuckles, along with concert photos of The Beatles and Elvis Presley.

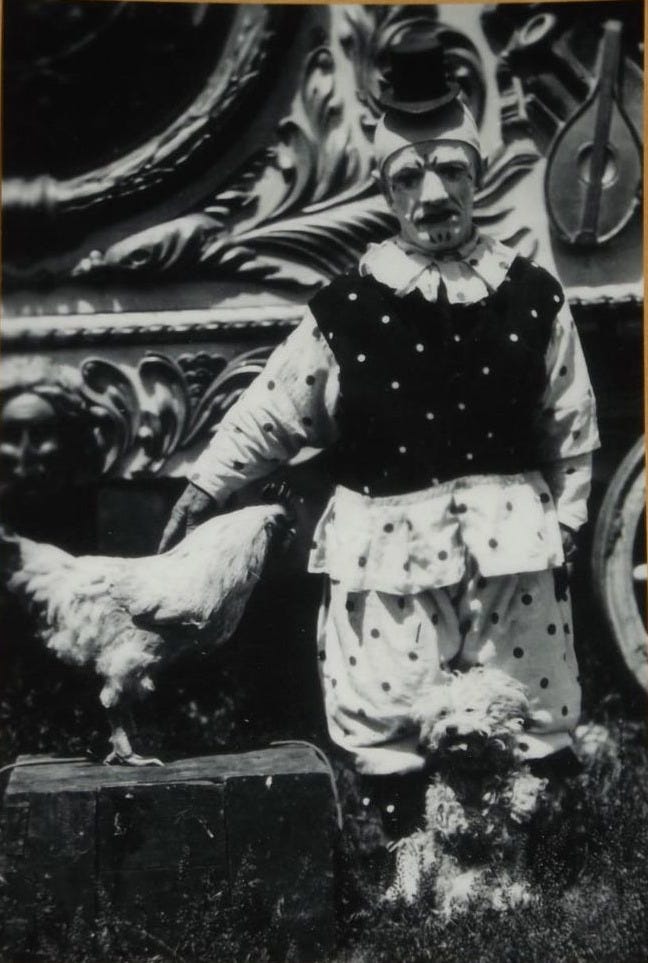

We got to our seats. Soon the overhead lights dimmed and the spotlights picked out the ringmaster, who stoked the crowd with his carny’s pitch. Then an old jalopy with a horn that went “kahooooooga!” raced out of the passageway where the Zamboni parked between periods. The jalopy made several mad laps around the centre ring before the driver slammed the breaks and the side doors flung open. Out tumbled two colourful balls that seemed to inflate when they hit the sawdust-coated floor: a pair of clowns in motley and wigs and make-up. Two more clowns followed. Then two more and two more, a posse of clowns so undersized that I mistook them for children.

Someone behind us said, “They’re midgets,” setting off a train of anxious associations that killed any joy in the spectacle. Midgets were undersized adults. They’d played the Munchkins in The Wizard of Oz, acting as comic relief to Dorothy’s more serious adventure. They were there essentially to be laughed at. So these clowns spilling out of the car were doubly set apart, by their makeup and outfits and by the bodies they’d been born into.

Why did those associations kill any joy in the jalopy gag? Probably because of all my childhood fears, the reigning king was the Fear of Being Laughed At, and all around me people were laughing, not with the clowns but at them. So I was relieved when the driver honked the horn, calling his brother clowns back to the jalopy, which had apparently stalled. The clowns capered back to the jalopy and began to push against the back bumper. The engine fired a few times without catching. Then it backfired, a sound like a gun shot, sending the clowns somersaulting backwards and earning the biggest laugh yet from the crowd.

Puffy pants were dusted off. Wigs scratched. But one of the clowns, lying near the exhaust pipe, writhed on the ground holding his hands to his body. The crowd’s laughter drowned out his screams. Eventually two of the two clowns pulled him to his feet. Another clown picked something off the ground, an object too small to identify. He dropped the thing into a colourful sack. Then he searched the sawdust until he found another, then another, and he put those things in his bag and ran toward the exit.

I can’t remember who put the clues together first. The backfire; the clown holding his wounded hand; the other clown picking several somethings out of the sawdust: they could only be severed fingers. By the time the wounded clown was carried off to the dressing room, everyone seemed to know.

There was a long interval, an eerie lull that reminded me of an interrupted TV program—the only thing missing was a placard reading, We are experiencing technical difficulties. I remember the hum of 15,000 people trying to formulate a response to the accident. Should they applaud, like when an injured hockey player was stretchered off the ice? Should they go home? No one did, not that I saw.

I barely registered the performances that followed, tedious displays of brute mastery, of the human body, of gravity, and of those poor dumb beasts—lions, elephants, monkeys—robbed of their dignity for a handful of peanuts. I kept going over the accident in my mind, returning to that moment of realization: Those are fingers he’s dropping into his clown’s sack. Can they sew them back on, I wondered. If not, will the wounded clown keep them as mementos of that terrible day? And why did I feel in some way responsible for the accident? Enigmas, every one.

When I eventually read Stephen King’s It, I was not surprised that he personified the hidden evils of small-town America as a tacky circus clown that singles out children for torment—I’d been carrying that bag of severed clown fingers in my memory for ten years by then.2 I was surprised to learn that my fear of clowns was shared by so many Baby Boomers and fellow Gen Xers, kids who’d grown up on TV, rock and roll, horror movies and comic books. We all would have liked to consign the circus clown to a dusty box in the attic, stashing it out of sight with the corsets, bowler hats, gramophones and irony-free TV variety specials of less wised-up generations. But these fears stand outside of time, and just as the corpse, no matter how undeniably dead, will surely move if you stare at it long enough, so too will the clown show you his real face when no one else is looking.

By the the early 1970s, this willingness to mock celebrity was emerging as the defining feature of the cutting-edge, post-Golden Age of Television sensibility. The creators of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-in, The Sonny & Cher Show, and even The Carol Burnett Show simultaneously embraced the Golden Age variety-show format while letting the audience know that they, too, knew how silly it was. Hollywood Squares was doing the same with the game-show format, with Paul Lynde—whom my friend Ray Robertson dubbed “Our generation’s Oscar Wilde”—subverting the tension with outrageously campy double-entendres.

And speaking of scary clowns, the best depiction in horror fiction of the essentially uncanny nature of the clown will always be Ramsay Campbell’s The Grin of the Dark, the story of a doomed film studies’ graduate who goes mad researching the lost films of a fictional silent-film comedian, Tubby Thackeray.