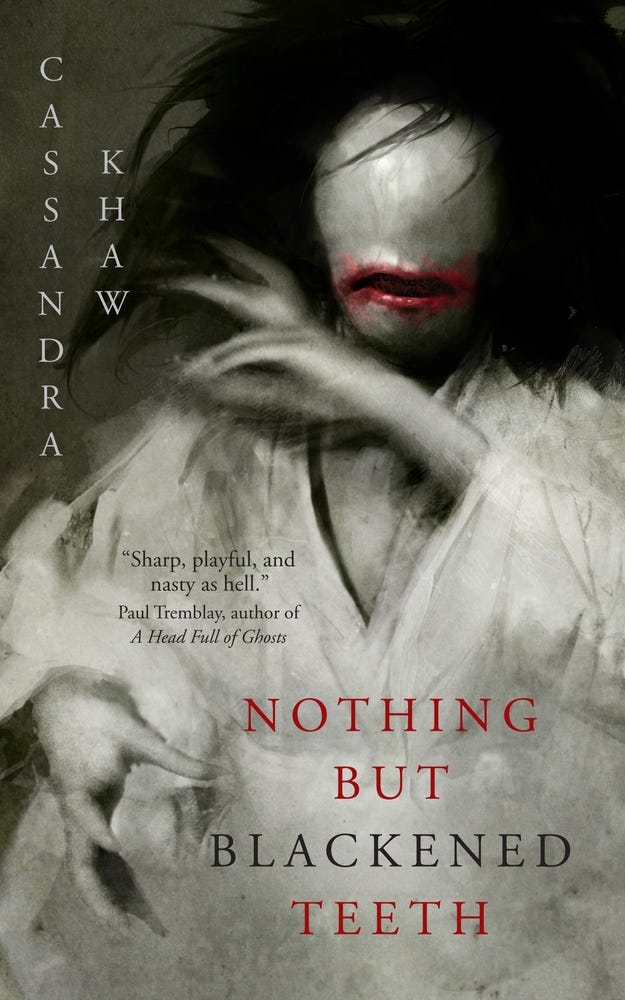

If a picture is worth a thousand words you might want to quickly scroll past the cover image of Cassandra Khaw’s Nothing But Blackened Teeth below. It’s the eyes—the lack of eyes—and the sensually engorged bloody mouth that makes the image (by artist Samuel Araya) lodge in the brain and whisper terrible things. A fitting image for the short novel inside, in which a widowed fiancé in Medieval Japan is voluntarily buried alive beneath the foundations of her betrothed’s family mansion as an act of mourning. Faithful retainers then bury live maidens under the house every year for several decades, feeding the hungry ghost with more hungry ghosts. Hundreds of years later, a wedding party of believably narcissistic twenty-somethings rent the decaying mansion for the night, where discover that snark and smart-ass banter are not enough to keep the hungry ghosts at bay. Violent mayhem ensues, pitting friend against friend, lover against lover.

Nothing But Blackened Teeth is Khaw’s first novel-length foray into horror. She is also the author of the genre-bending sci-fi novella The All-Consuming World and many short stories. Khaw spoke to The Veil from Montreal.

The Veil: How did you become a horror fan? Did it happen when you were a kid or later in life?

Cassandra Khaw: Very young. Part of it is that I was born and raised in Malaysia, a country that’s steeped in superstition. Everyone has a haunted house story and everyone has a tale of something supernatural that they’ve encountered. While not intensely religious, it’s a country with a lot of ethnicities and a lot of cultures, and everyone is very well aware of their own traditions and the traditions of others. Every year we celebrate what is called The Hungry Ghost Festival, when it is believed that for a month the dead are allowed to walk among the living again. So people do things like erect massive stages where they perform deep into the night for the dead who are, I guess, on holiday. When you grow up in an environment like that, it’s hard not to be intrigued by horror.

This tendency was emphasized by my parents, who had this really weird thing where when I was between the ages of seven and nine, for reasons I still don’t understand—maybe it’s because they are not good people—they insisted I watch, with my eyes open, all sorts of horror movies. I watched John Carpenter’s The Thing, without closing my eyes or plugging my ears, at the age of eight! As you can imagine, it left an impression with a capital “I”.

The Veil: Did you have nightmares?

Cassandra Khaw: I still do about certain scenes occasionally. Like the one where the doctor is investigating one of the victims and a big mouth opens up in the victim’s stomach and bites off the doctor’s arms at the elbows. All of this left a lasting impression and I guess the idea of monsters just seeped into my head.

The Veil: In a recent interview you said to the effect that, in the West haunted houses are an anomaly. Whereas back home in Malaysia, you’re told from a young age that there is likely some entity living with you in the house. What would those entities be?

Cassandra Khaw: They could spirits of the dead or djinn. There’s not a standardized belief, per se, but in Malaysia people believe that there are different layers to reality. Not everyone believes in ghosts, not literally as far as I can tell. But for instance, if you can’t see bacteria, it stands to reason that there are other things that we cannot see, and if we can’t see them and they don’t bother us, do we need to investigate? That’s more the approach. Most people believe there is some form of something that we co-habitate with.

The Veil: I experienced something similar with my mother’s Irish Canadian Catholic family, but I don’t think that’s the norm here.

Cassandra Khaw: North America is very different. It’s so young as a culture, but also so weirdly detached from the immigrant cultures that grew it. North America needs more answers than older countries, if that makes sense. And science and engineering are such tent poles in North America, that it makes us very binary in how we look at the world. I don’t mean this in a bad way, but for example, I read several articles by North Americans talking about how Japan was the most secular country on the planet. That fascinated me. The idea was that, because in Japanese culture almost nobody explicitly worships anything—there’s shrines and traditions, but their beliefs are not set—then the Japanese are therefore not religious. I don’t think that’s true, but to many North Americans, it appears to be. The idea of grey is still a new thing over here. It’s not a new idea in older countries like Japan.

The Veil: And how did you move into writing fiction? You have a background in tech, which is not something most fiction writers can say.

Cassandra Khaw: I was living in Malaysia and working in AI when a friend asked me to design a website for him. After that, he asked me if I wanted to write an article for the site. I said, Sure, not knowing how to do any of that, so I wrote the article, and to no one’s surprise, no one in the world gave a flying poop about it! But that got it into my head that I was all the way over there in Malaysia and all the people who matter—so to speak—were in America. So what I needed to do is talk to all the editors and all the people there until someone paid attention to the things I was writing. Being a very unwise but bullheaded twenty-four year old, I flew to San Francisco to attend a gaming conference and crash on the couch of a friend whose picture I’d never even seen. Today as an adult I think, You could have been killed, what were you doing?

So I followed the conference circuit and got my start in journalism and wrote for magazines like PC Gaming. Somewhere along the way I made friends with a dude who worked at a video game company that went into publishing. He asked me to do some business development work for them and got to know a game developer. He knew I wasn’t a book or game writer but he asked if I wanted to help out with a game he was creating. Together we created a cute little puzzle game called “She Remembered Caterpillars” that is also about invasive brain surgery. It won a Best Kids’ Game award in Germany, surprising all of us! From there, one thing led to another in the games world, and I slipped into writing fiction as well. I wrote some short stories and people took notice of the work, and so more and more people were willing to take a chance on me. My profile grew in both areas and I started getting more offers to write.

The Veil: So how did you come to write Nothing But Blackened Teeth?

Cassandra Khaw: It has a kind of bleak origin. When I was about thirty-four, my mother let me know that my father had passed away from a.heart attack. So I told her I would cancel everything and get a plane ticket home, but she shocked me by saying, Oh, don’t bother coming home, we’re scattering his ashes today. It floored me to have that ritual of goodbye taken from me, that sense of closure, which is what every funeral is. So I spent about a year completely unmoored, but with the help of people who love me I started getting my bearings again. Precisely a year to the day later, my mother said, Actually, your father hung himself in full view of the street where his shop was. And I was like, Sorry… The macabre funny part is that I told my mother that we’re going to therapy tomorrow, and getting professional help to deal with this!

So Nothing But Blackened Teeth started while I was recovering from that second blow. I was home in Malaysia and life was difficult there because my family is quite abusive. Being trapped in a house where so many dark things had happened, the writer in me needed to literalize that. I slowly and listlessly wrote it while I was going through therapy. Cat [the novel’s protagonist] embodies a lot of my grief and that weird thing that happens when you’re still mourning after that set period in which you’re supposed to grieve. I had assumed people would accept that grief takes as long as it takes, but after a year, I had people looking at me funny and saying, I thought you were done with this. Why are you still sad? So Cat holds a lot of my feelings in being a person-shaped thing while still having her heart broken by the world. Eventually I started to feel better and put the work aside, but then Ellen Datlow [the author, editor and horror anthologist] being Ellen asked me if I had a book for her. I had hardly even finished the book but I handed it over to her not knowing what else to do with it. She took it and a few months later I got an email from her that began, “Don’t panic: I really like the book.” Then she sent me eighteen pages of edits! I immediately sent an email back to her and said, “I’m really glad you began your email with, Don’t panic.”

The Veil: I would imagine that the claustrophobia in the novel, the sense of being buried alive and imprisoned in a house, must have really spoken to you when you were mourning. You have all these women literally buried alive, but not quite dead, because of the death of a man.

Cassandra Khaw: The claustrophobia was definitely something I wanted to work with. I am claustrophobic. I can’t stand window seats on an airplane—I will claw at the walls and scramble over the seats to get away from them. Yes, so much of the book is about capturing that feeling of suffocating in your grave and not being able to speak about it. Holding it in.

The Veil: You also weren’t afraid to make your characters unlikable and believably selfish at times. They are certainly relatable, but when the chips are down, the characters mostly resort to their worst selves. Were you were afraid of putting off readers? Did that even occur to you?

Cassandra Khaw: Well, I’m thirty-seven: I’m too old to enlighten anyone about how human beings really are. When I was younger I might have tried to push the idea that we are innately good, but especially looking at the world the way it has gone recently, it’s clear that we often resort to our basest instincts. I don’t think that’s always a bad thing, I don’t think it’s indicative of any inherent evil in people, but it’s often the parts of us that bite back, that snarl and show their teeth, that keeps danger away, even if there are better ways to deal with it. I wanted to tell a story where people are pushed to the breaking point and are allowed an excuse to acknowledge the worst in themselves. There are far too many books that assume optimistic things about human beings. I wanted to remind people that we often make the bad choices. I believe we are capable of great things, but in this story I wanted to show how we’re capable of the worst and then lie about it to ourselves.

Was I afraid when I was writing? I don’t think so. I was definitely expecting some people to not be happy. I’ve seen some reviewers who are very unhappy about the fact that there are unlikable human beings in the world! They’re very mad at me! In the climactic scene [in which a character is gruesomely murdered] I have the other characters just standing around doing nothing. I’ve had people email me saying, What the hell, no one does that. No one would just stand around while someone is dying. But if you look at how people react to violence, if you look at how women turn aside when they hear a slap or a woman screaming. It’s what we do because we’re cowards. The shock sets in and we just watch, frozen in place. I don’t think we can really understand people until we understand just how dark we can get.