Horror is the only genre named after an emotion, and it exists to elicit that emotion. It exists to scare you. The best horror stories also conjure feelings of awe, wonder, suspense, relief, pity, comic relief and the sense of communion that comes from the shared experience of those emotions. But if doesn’t scare you at some point, the movie or novel or story is either a dud or should probably be classified in a different genre.

The experience of horror and terror also leaves an imprint on the nerves, which is why most fans can tell you exactly where they were and what they were watching or reading when they became a devotee. (Even haters can recall the movie or book that made them avoid horror.)

If you’re like me, your initiation into horror fandom probably wasn’t consummated at the altar of one of The Greats—The Exorcist, Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street—but at a more downmarket location, watching some forgotten or overlooked B movie that you can’t erase from your memory.

I know where I was…

In the early 1970s of my memory, everybody on my street is dressed for a countercultural “happening,” a free music festival or spontaneous guerrilla theatre performance in the local park. Not that I’d ever attended such happenings or knew anyone who did. Hippies, according to my mother, were lazy dropouts who were ruining it for everyone else—what “it” was and how the hippies were ruining it needed no explanation. As for my bartender father: if he’d never beaten up a hippie, it was only for lack of opportunity.

And yet we kids went to school wearing a motley of polyester and cotton, the girls in bright patterned dresses with primary-colour tights, the boys in a rainbow of corduroy. My teenage cousins and their friends all had long shaggy hair, wore faded jeans and listened to Cheech and Chong albums, and even the characters from our favourite kids’ shows—The Banana Splits, HR Puffenstuff, Scooby Doo, The Electric Company—drew their outfits from a hamper of curtain samples, pyjamas, gypsy scarves and the wardrobes of lounge singers. It was as if the dying remnants of the sixties counterculture were off-gassing rainbows of psychedelic colour into the atmosphere.

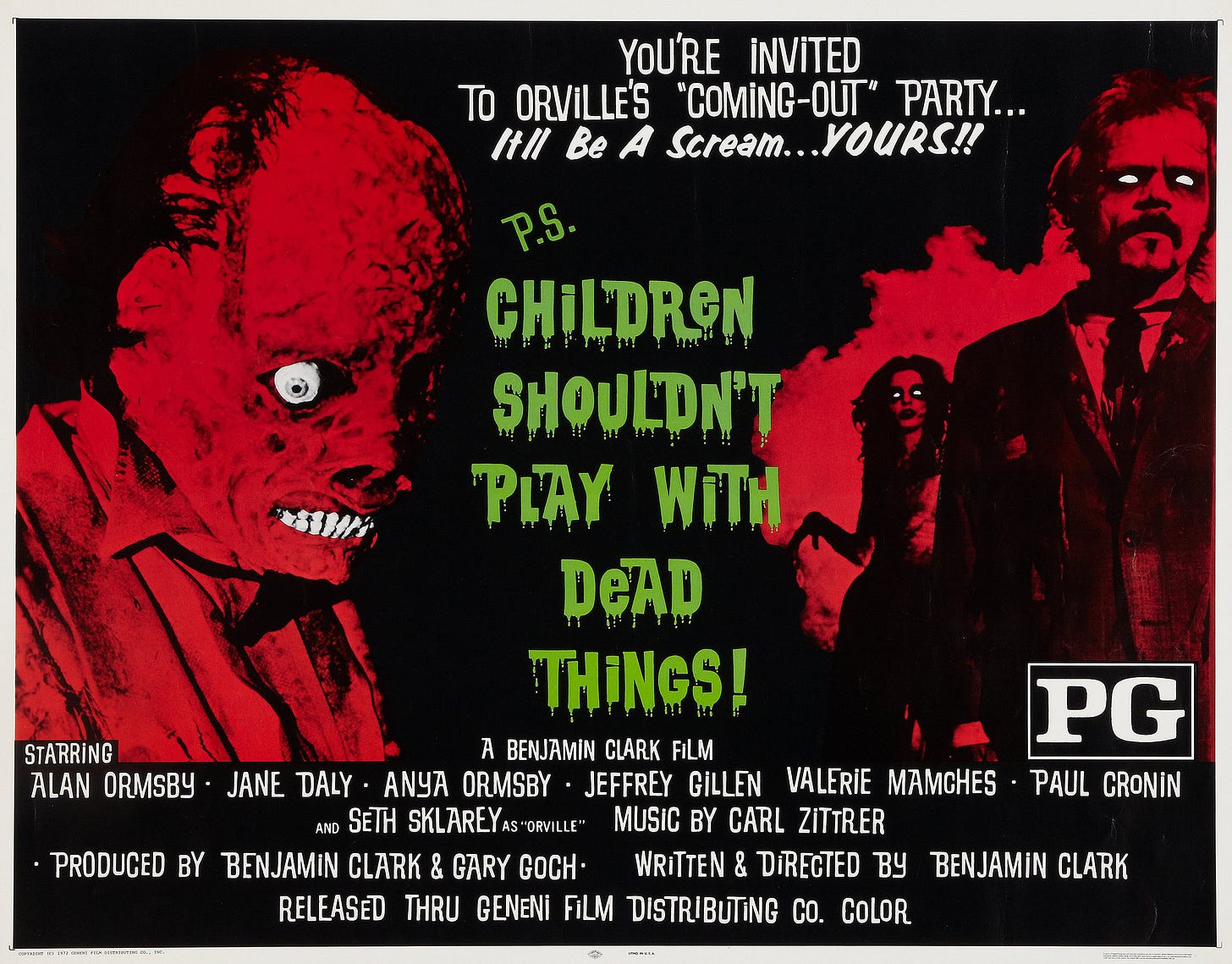

All of this is to say that I was primed for Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things, the 1972 directorial debut of Bob Clark, who went on to helm Black Christmas (in my opinion the greatest slasher flick of all time). Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things was made to cash in on the success of Night of the Living Dead and other graphically violent, downbeat shockers of the emerging New Horror movement, but it delivered a radically different experience.

Me and the other 300 or so kids who piled into the movie theatre that chilly Friday in 1973 to watch Children had no idea what we were in for and wouldn’t have cared anyways. After wolfing down our dinners, we’d ran/shuffled/somersaulted to the nearby Canadian Forces Base, a monolith of barracks, low buildings, empty fields and airplane runways sealed behind a high, barb-wired fence. “The Base” as we called it was off-limits to us civvies, but on Friday evenings the guard-house gate was thrown open to the local kids to watch a movie at the on-site theatre. Admission was fifty cents, popcorn and a drink another two bits, money my brother and I pilfered from the tips my father spilled onto the coffee table when he got in at 2am from work.

People under the age of fifty may find it hard to grasp the sheer awesomeness of living near the equivalent of a rep cinema in the early 1970s. Home VCRs were still the stuff of science-fiction, and a cable hook-up, if your family could afford it, brought in a paltry twenty channels, most of the air-time taken up with staid melodramas, made for TV movies, and syndicated sitcoms. If you were lucky enough to catch a cool movie on your blurry three-colour TV screen, it was sliced and diced by network censors and interrupted by local furniture store ads.

Friday night at The Base was our education in cinema as well as a window into the world beyond our working-class North York neighbourhood, where when the wind blew right you could smell the cow manure from the nearby farmland. On Friday night there were no ads, no censors, and no parents or siblings to try to change the channel or tell you to go to bed. Huddled together in the dark, we watched trucker and Blaxploitation movies, kung fu epics (Bruce Lee = god), Hammer horror pictures, concert films (Welcome to My Nightmare, Gimme Shelter), rock musicals (Tommy, Phantom of the Paradise), gritty crime dramas, and the occasional screwball comedy.1

The Friday night master of ceremonies was an apoplectic career officer (nicknamed “Sergeant Rock” by the smart-ass teenagers) who warned us not to rip up the seats or piss in the bathroom sink before he introduced the night’s movie. The lights went down and we were treated to a reel of schlocky trailers that were often better than the film we were about to watch. Then the screen went black, and in those delicious moments of almost total darkness, teenage boys terrorized us with extended wolf howls, ghostly moans and other sound effects from Hollywood’s Golden Age picked up from late-night TV.

A series of grainy shots established the setting of that night’s offering: a tropical island, barely lit by the moon overhead. A crotchety caretaker appeared, lured from his tiny cabin to investigate a disturbance in the island’s dilapidated graveyard. His cornpone accent got the crowd giggling, and when he was knocked unconscious and tied up by two men, the audience settled into their seats, ready for ninety minutes of conventional thrills, chills and laughs. The kitschy, neon-green opening credits and the film’s wacky title—Children? Dead things?—pumped up the House of Horrors fairground vibe even more.

After the caretaker was safely tucked away, the human voices gave way to discordant, atonal blasts of synthesizer. Poor lighting, choppy editing, and bizarre camera angles obscured much of the action, but we could now see the two attackers more and less. They wore evening wear and grotesque face paint, as if they were the sole guests of the world’s worst Halloween party.

Then shit got weird.

As the men began to dig up a coffin, the soundtrack of grating synth noise and the artless camerawork obliterated whatever was left of the carnivalesque tone. Without speaking, the men removed a corpse from its unearthed coffin and propped the body against a tombstone. Then came what was for me, an eight-year-old already prone to claustrophobia, a terrifying moment: one of the men got in the coffin and let his accomplice bury him alive.

From there the plot, as threadbare as the knees of my favourite blue cords, staggered into action. A sailboat glided into the island’s dock, while in the distance, across a dark body of water, a city’s lights twinkled without warmth. Alan, a goateed hippie in a bright orange shirt, cravat, and striped pants, walked onto the dock and haughtily ordered an off-screen minion to hand him a lamp.

As the other characters—a half-dozen young actors dressed in bohemian thrift-shop splendour—emerged into the glaring, shadow-riven light, the bickering and backstabbing began. Alan, it turned out, was a monstrously egotistical theatre director of meagre talent who’d forced his troupe of young, unemployable actors to join him for an overnight expedition to the island graveyard. There he intended to perform an occult ritual—for real or for laughs was unclear.

As the theatre troupe unloaded the boat, I realized that the actors were not only dressed like my older cousins and their friends, they talked like them, too, mocking authority with the same slangy putdowns while flirting and teasing each other. The actors on screen were more flamboyant, sophisticated, and nasty than anyone I knew, but that only made them more believable, as if this was how the cool kids talked when there were no children or proper grown-ups around.

Alan then forced his minions to dig up a grave. Was this the same grave the mysterious duo had dug up and filled in earlier, I wondered? Hell, yes! No sooner was the coffin uncovered when the man inside “came to life” and attacked the troupe, scaring the actors so badly that one of them pissed his pants, a realistic detail that shocked me. This zombie gag proved to be the first and most harmless of Alan’s stunts, which became crueller and more depraved as the evening went on. The next, in which Alan and his Manson-girl acolyte Anya perform an occult ritual to raise the dead, fizzled out, to the delight of the troupe.

Still, I was gripping the arm rests on my chair as if my life depended on it. I’d seen enough horror movies to understand that I was watching a very different kind of film. There were none of the genre’s comforting framing devices—castles, laboratories, haunted manors, family curses, priests, or mad scientists—to remind us that this was, after all, only a movie, and no lush orchestral score to cue the scares. Even the graveyard setting, which was straight out of an old Bela Lugosi movie, was stripped of reassuring signifiers. Maybe it was the combination of bad lighting, suggestive scene framing, and disorienting camera work, but the graveyard and the island setting were both realistic and archetypal, like the setting of a nightmare—the hippie troupe might well have just crossed the River Styx to the land of the dead.

After the ritual failed, Alan led the actors—and the actual corpse, “Orville”—to the caretaker’s cabin for a party. There the movie morphed into a bizarre cross between Night of the Living Dead and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Half-willing participants in “Orville’s coming-out party,” the actors relentlessly mocked each other and the corpse as Alan and Orville are wed in a blasphemous ceremony.2

Meanwhile, out in the graveyard, the two gravediggers were filling in the twice-opened grave. More bad puns were exchanged. They were the last jokes in the film.

Alan’s occult ritual, it turns out, was more effective than his minions gave him credit for. In an extended sequence that even after repeated viewings still shocks me, the corpses dig their way out of their graves to the accompaniment of those blurting, shrill synth noises. The anonymous bodies shudder and moan, contorted in what might be agony or sexual ecstasy. Close-ups of rotting faces and bulging eyeballs are cross cut with over-lit long shots of multiple corpses taking their first steps, their bodies jerking and swooning in a parody of modern dance. 3

It amazes me that I didn’t piss my pants or run from the theatre screaming. I didn’t just watch that terrible scene, I lived it as the passive “I” of a nightmare helpless to alter the events, my loss of amplifying my sight and hearing.

It got so much worse. The gravediggers were torn apart—not bitten on the neck by a dapper vampire, or bloodlessly crushed by a radioactive monster, but eaten, bloody flesh chunk by bloody flesh chunk.

The film’s final act pitted the zombies against the surviving actors, who, lacking any shared ethics or survival skills, quickly turned on each other, leaving the zombies to pick them off one by one. No catharsis was forthcoming. How could it be? Even as the hippies were hunted down and eaten, I was still asking myself, Who are the real monsters here? Whose side am I on? Only Orville, who endured so much humiliation, and Anya, Alan’s earnestly gullible acolyte (who also resembled a girl I had a crush on), won my sympathy.

With everyone else dead, Alan and Anya ran upstairs to make their last stand. The dead, having broken into the cabin, followed them up the staircase, where Anya stood with Alan, his face a mask of sly calculation. Without a hint of regret, Alan pushed Anya into the arms of the zombies. In a gruesomely funny moment, the zombies briefly suspended their attack. Alan was such a selfish shit that he offended the worm-eaten dead.

I’d never been so shocked by a scene in a film. I was repulsed, angry, and yet a subterranean connection seemed to open between Alan and me. Alan had done the unthinkable, but would I have acted with any more honour? Wouldn’t I, in his position, push a family member or friend into the arms of the dead to save myself?

Alan rushed into the bedroom, where he found Orville, who’d been laid on a mattress after the wedding, now very much alive. Embracing Alan in a manly hug, Orville took his dignified revenge by bending Alan backwards and breaking his back.

When I left the theatre with my brother and our friends I couldn’t join my brother and our friends in the usual post-movie joshing. I was shattered, possibly traumatized by what I’d seen, and yet all I could think was, “When can I watch it again?” For months afterwards I replayed scenes in my mind at bedtime, the zombie who feasted on one of the hippie’s guts, Alan pushing Anya down the stairs, Orville silently rising from the stained mattress to kill his tormentor. One afternoon while listening to a K Tel album (Sound Explosion: 22 Original Hits), I decided that Tony Orlando and Dawn’s “Say, Has Anybody Seen My Sweet Gypsy Rose,” a melodramatic ballad about a woman who leaves her family to join a burlesque show, was actually about Anya. In my version, Rose’s real name was Anya and instead of joining a burlesque show she ran away to join Alan’s theatre troupe. The ballad singer, Rose/Anya’s heartbroken husband, believes she is still alive, but because I’d seen Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things, I knew the real story.

In other words, I was hooked, hooked bad. Ever since, whenever I watch a horror movie I haven’t seen, I’m hoping to relive that hundred or so minutes back in 1973. It never quite happens, but it might, one night.

Some of the movies we watched at The Base symbolically rang the long overdue death bell on the Summer of Love, none so earnestly as Billy Jack, the drop-dead best friggin’ movie ever made according to anyone who mattered on my street. Billy Jack may have been a hippie lover, but he was a Vietnam vet, martial arts expert and Native American mystic who kicked the shit out of rednecks, crooked cops and snotty rich kids.

I don’t think my adult self is reading too deeply into the film’s subtext to see the hippies’ desecration of Orville, who like the grave robbers is dressed in formal evening wear, as a metaphor for the countercultural condemnation of all inherited institutions and social mores. The hippies are literally flogging the dead horse of bourgeois marriage. In doing so, they are revealed not as bold revolutionaries but bickering nihilists who desecrate graves and corpses for deviant kicks. Hippies, the film argues, are self-absorbed hypocrites whose politics mask a selfish unwillingness to grow up. Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things is either a very reactionary film or a slyly subversive one, depending on your politics.

Looking back, I realize I was also experiencing the second emotion (after terror) essential to the best horror: the feeling of awe in the face of the mysterious or unknowable. In those moments I believed I was watching the life cycle crudely reversing itself, of a new life emerging not from a womb into the loving arms of its mother, but from the cold grave into an even more barren world. As HP Lovecraft wrote, “The one test of the really weird (story) is simply this—whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.”

When I was about seven or so, our family went over to another families house for a get together. The kids piled into the TV room and somehow, IT ( the Tim Curry one) was chosen to put on. Now, no adults knew what was happening and maybe in retrospect that makes it scarier. I don’t remember one specific scene other than the teeth of the clown.

The feeling that the movie pulled out of me lasted for I feel like years. Immediately after getting home later that day, I started taping my bedroom closet doors shut ( so in my child’s brain I could see if the tape was broken in the morning), stuffed things with under my bed so nothing could hide under and I used to put my toothbrush in the bathroom sink cabinet handles each night so that nothing could get out of the sink. This, I feel, continued for years. Also, I never told anyone about my fears. Why I’m not sure.

Needless to say, I feel like I was terrified and my imagination of what could happen scared me even more.

I’m not sure that it turned me into a horror fan but definitely made me aware of the idea of scary movies & that lasting feeling. It would be years upon years later when I would seek out a horror movie of my choosing.

James, after 40 years I now get your insatiable desire for all that horrors you.

When I was eight I happened by chance upon 'Don't Be Afraid of the Dark' (1973) --a made-for-tv movie horror flik featuring menacing goblin-like creatures (described by some as little teddy bears with coneheads) that hid away under the fireplace when they weren't terrorizing the inhabitants of the house, cutting them and dragging them to their deaths. Only bright lights could stave them off. One scene has the desperate heroine catch being dragged to her certain doom, but she is trying desperately to grab hold of the flash camera on the way...That one stayed with me. Guillermo del Toro too I hear, as he made a remake.