Send Out the Clowns

A few thoughts on the sinister quality of clowns, fortified with a gruesome anecdote

When my brother Steven and I were kids we used to scour the TV guide for news of the next The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast, a program that appeared irregularly on NBC for several years in the 1970s. For those who missed out, Las Vegas legend Dean Martin would gather together a handful of his Hollywood buddies into the MGM Grand Hotel’s Ziegfeld Room, where they turned their comedic talents on the evening’s “roastee.”

Never mind that we didn’t always get the jokes: for one golden hour, Steven and I got to watch the stars of our parents’ generation—Milton Berle, Lucille Ball, Red Skelton, Don Rickles—act like children at a sugar-fueled birthday party. They backslapped, they pounded the banquet tables, they chugged highballs and wiped tears from their laughter-flushed cheeks as schoolyard insults rained down on the chosen victim, who was given a five-minute slot at the end of the roast to return the affectionate abuse. At home, we guffawed and chugged our Cokes like a pair of high-rollers waiting for our turn at the podium.

The good-natured ribbing was also transgressive in a way we couldn’t define. The guests on Dean’s roasts had exchanged their familiar masks—that of the hyper-positive, always-on celebrity—for a more interesting one: the sadistic, childish imp who secretly hates his or her fellow celebrities’ success. Like our parents and relatives at a drunken family gathering, the adults were ceding their adult roles for a few hours to revel in impulse and play.

Dean’s buddies, if they really were his buddies, had taken on the traditional role of the clown, breaking all societal restraints to loudly and publicly speak the unspeakable. They even wore garish outfits worthy of a clown, tuxedos with frills the colour of cake icing, velvet smoking jackets, sequined ball gowns accessorized with bizarre hats and purses. The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast affirmed the “phoniness” of its participants while reasserting their status as celebrities, because you had to live the conventions of celebrity to mock them. Just as our parents would be nagging us the day after the party to clean up our bedroom, so Dean’s guests would soon be seen shilling their latest projects on the talk-show rounds with practiced enthusiasm.

This ritualized clowning in no way endeared us to the fright-wig-and-silly-shoes circus clowns that stalked low-budget local TV kids’ shows like Romper Room or The Uncle Bobby Show. Watching a man or woman in grease paint and a baggy body suit throw confetti in the air was about as funny to us as the fusty Annie and Gasoline Alley comic strips in the newspaper funny pages. It wasn’t so much that traditional clowns were out of date or unhip—all the neighbourhood kids loved old-time comedy staples like The Three Stooges and The Little Rascals—but that we had no reference points for them. We didn’t know what rules the clowns were breaking, what they were making fun of or why, and because traditional clowns don’t speak, we had no way of getting up to speed. The clowns’ antics meant as much to us as the actions of a stock character in an Italian opera. The circus itself, where most clowns performed, also seemed hopelessly antique, a relic of the pre-TV era when you had to get dressed up and leave your house to be entertained. By the 1970s, at least for us urban and suburban kids, the old dream of running away to join the circus had been eclipsed by a hipper fantasy: taking our place beside the chain-smoking clowns on Dean Martin’s TV carnival.1

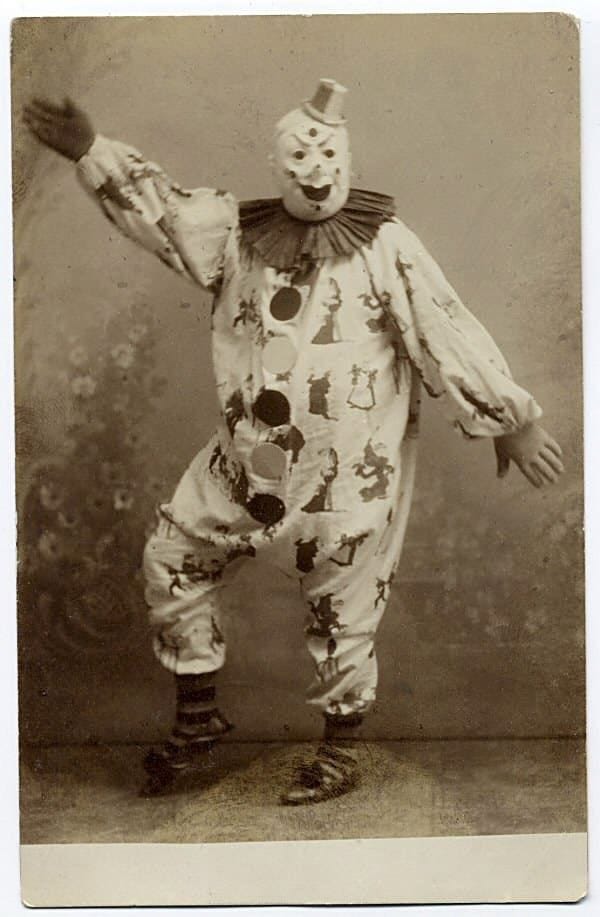

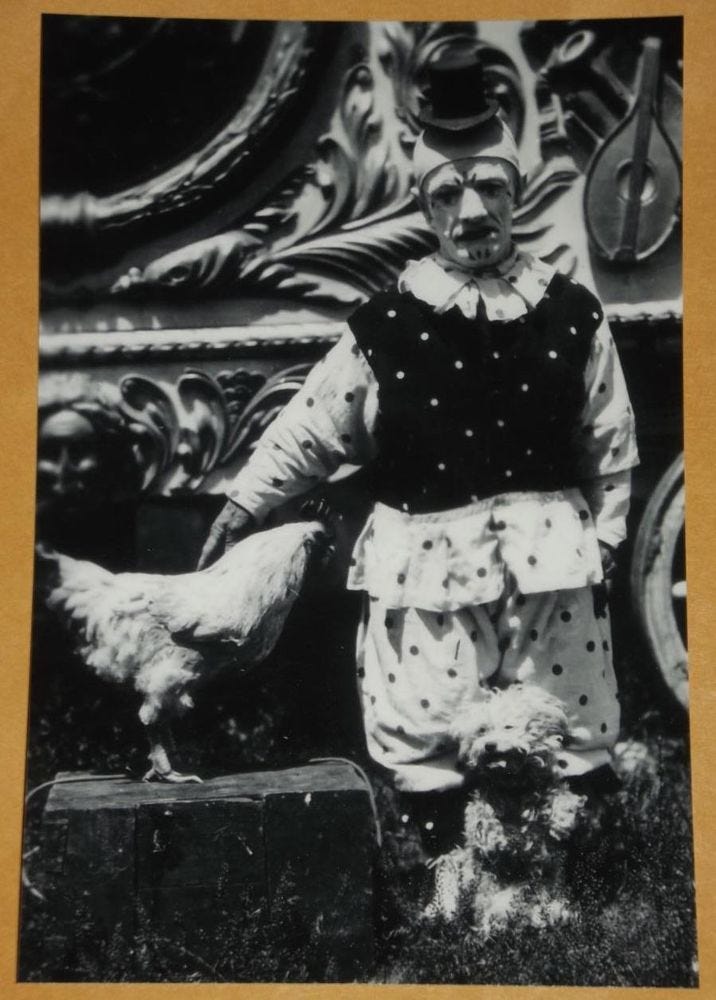

As Freud and a thousand other commentators have pointed out, there’s also something uncanny about traditional clowns. Clowns are scary.2 They’re not only mute, their inability to follow the simplest directions hints at a willed deafness. It’s true that children also pretend not to hear things, but only to achieve an aim, like getting out of a chore or avoiding a scolding. Clowns don’t seem to understand any commands, just as they can’t pick up any object without dropping it. Clowns are clearly out of control—they can’t even line up their emotions with the happy or sad expressions they’ve poster-painted on their faces. This makes clowns not only inscrutable but unknowable, a quality that alienated us wised-up TV kids.

So it was that I approached my first trip to the circus (some time around 1975) with an attitude of mild expectation and aggrieved resentment that my father, a whiz at procuring freebies from the regulars who lined the stools where he tended bar, hadn’t nabbed us tickets for a hockey game or wrestling match instead. On the plus side, the circus was at Maple Leaf Gardens, one of the three secular shrines of my childhood (along with the Royal York Hotel, where my father worked until 1973, and the Royal Ontario Museum).

Walking the Gardens’ crowded corridors with Steven and our mother, I took in, through a cloud of cigarette smoke as thick as cotton candy, the familiar black and white photos on the walls, the pantheon of toothless hockey players, the heroes of my uncles’ childhood, baptized in champagne by old men in fedoras in the Maple Leafs storied dressing room. There were prize fighters with bright eyes encased in swollen flesh and wrestlers in Speedo prototypes flying from the turnbuckles onto prone opponents, and concert photos of The Beatles and Elvis Presley.

Our seats were situated about a third of the way up the stadium’s sheer-cliff sides—if you leant forward too far you felt like you’d drop you into someone’s lap in the next row. I clamped fingers onto the arm rests, then gazed up at the Gardens’ vast pyramid ceiling, encrusted with metal gangways, staircases, hanging floodlights and dangling cables, the infrastructure tinted the hue of a chain-smoker’s fingertips. Though I was terrified of heights (and still am), I never tired of imagining bounding up the gangways to swing across the chasm of space above the ice on a stray rope, then shimmying down the light cables to dangle above the centre-ice dot. Maybe one of the acrobats would pull off that feat today, I thought. I’d never seen that on TV…

The lights dimmed and the ringmaster stoked the crowd before introducing the first act, his carny’s pitch drawing me forward in my seat as a riotously colourful jalopy with a horn that went “kahooooooga!” came racing out of the passageway where the Zamboni normally parked between periods. The jalopy made several mad laps around the centre ring. Then the driver slammed the breaks. The car doors flung open. Out tumbled two balls of pure colour that seemed to inflate when they hit the sawdust-coated floor: a pair of clowns in motley and wigs and make-up. Two more clowns followed. Then two more and two more, all of them so undersized that I mistook them for children. I heard someone behind us say “midgets” and I understood: the clowns were like the actors who’d played the Munchkins in The Wizard of Oz, ordinary adults who’d never outgrown the dimensions of childhood.

The goodwill generated by the Gardens’ atmosphere vanished. People were laughing at the clowns before they’d even begun their shtick: they were laughing because the clowns were midgets. The clowns must have known this. Of course they did. So how they could roll out of that car day after day knowing that thousands of people were going to laugh at them?3 Clowns were not only uncanny, it seemed, they were downright perverse. They invited mockery, perhaps even craved it.

On the other hand, the clowns were funny. They somersaulted and bumped into each other and so exasperated their leader that he tried to pull his hair out. Laughter is infectious: everyone else was laughing, so I did too. The capering continued until the driver honked the horn to call his brother clowns back to the jalopy, which had stalled, on cue no doubt. The clowns crossed their arms and scratched their wigs and fell into the sawdust, but eventually they reached the jalopy’s back bumper and began to push. The engine fired without catching a few times. Then the jalopy backfired, a sound like a gun shot, sending the clowns somersaulting backwards and earning another big laugh from the crowd.

Puffy pants were dusted off. Wigs scratched. But one of the clowns, stationed near the exhaust pipe, now lay on the ground holding his hands to his body. The crowd’s laughter must have drowned out the fallen clown’s screams because the other performers were still gamely pushing the stalled jalopy. Finally one of the clowns rushed back to his companion and pulled him to his feet. Another clown picked something off the ground and placed it in a colourful sack. Then he searched the sawdust and found another thing, then another, and put them in his bag.

It was the fallen clown’s fingers. This was not part of the act.

They clowns carried the injured man to the now idling jalopy, which raced toward the exit. There was a long interval, an eerie lull that reminded me of an interrupted TV program—the only thing missing was a placard reading, We are experiencing technical difficulties. I remember the hum of 15,000 voices as people tried to formulate a response to what they’d just witnessed. Should they applaud in support, like when an injured hockey player was stretchered off the ice? Should they go home?

I was too worried about the clown’s dismembered fingers to care. Since they couldn’t be sewn back on (I believed), the fingers would either end up in a garbage can or, worse, pickled in a jar for display at one of the freak shows celebrated in the piles of Ripley’s Believe It or Not comics I liked to read at my Uncle Nick’s cottage. Both options overwhelmed me with pity, less for the clown than his dismembered digits, which, lying there in the sawdust illuminated by the circus lights, had looked as forlorn as a kid separated from his mother in a shopping mall. If only the accident had happened backstage, I thought, it wouldn’t have been so bad. If he’d blown off his fingers in the presence of friends, the clown could have have turned the accident into a hilarious anecdote—that’s what my father would have done. The fifteen thousand spectators cut off that avenue to the clown and his fingers. We were not his friends, and his role as clown precluded the powers of speech.

I barely registered the performances that followed, tedious displays of brute mastery, of the human body, of gravity, and of those poor dumb beasts—lions, elephants, monkeys—robbed of their dignity for a handful of peanuts. On the way out of the stadium, people wondered aloud if they’d really seen the fingers lying in the sawdust. I had, and I suspected—correctly, as it turned out—that I’d carry the clown’s dismembered fingers in my memory like the incriminating evidence of a shocking crime for which I bore some distant but inescapable culpability.

When I eventually read Stephen King’s It, I was not surprised that he chose to personify the hidden evils of small-town America as a tacky circus clown that singles out children for torment—I’d been carrying those severed fingers in my memory sack for over a decade at that point. I was surprised to learn that my fear of clowns was pretty well universal, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and those that followed. King’s geeks and bullies were TV kids like me and my friends. They listened to rock and roll, chewed bubble gum and read comic books, and they’d have liked nothing better than to consign the circus clown to a dusty box in the attic with the corsets, bowler hats, gramophones and patent medicine bottles of older, less wised-up generations. But the past is never really the past. Just when we think we’ve escaped its reach, it slaps on a layer pancake make up and dons a blood-red wig to scare the crap out of us.

Or, for that matter, the hijinks on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-in, The Sonny & Cher Show, The Carol Burnett Show or, for the older kids in our neighbourhood, Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. My own dream was to one day usurp Paul Lynde—whom my friend Ray Robertson dubbed “Our generation’s Oscar Wilde”—from the centre square box on Hollywood Squares.

How clowns ever became children’s entertainment staples remains an enduring mystery, no matter how much I read up on it.

As the child of an alcoholic parent, I was morbidly attuned to any situation with the potential to cause shame. For instance, I’d have chosen the scariest, most violent horror film over watching an episode of Candid Camera. It was shameful enough to be tricked while on camera, but to allow the footage to be shown on national television? I’d have rather died.