There was a time not long ago—say, July 2020—when you could have been excused for not having read anything by the American/Blackfeet author Stephen Graham Jones. Yes, he already had more than two dozen books under his belt, but because of his penchant for throwing genre conventions and postmodern narrative tropes into an intellectual Vitamix, he tended to be pigeon-holed as a writer’s writer or an experimental writer. Not that that characterization was a bad thing, but it missed just how fan-friendly his fiction has always been. Jones is, first and foremost, a diehard fan of the genres—horror, sci-fi, fantasy, detective, western—he threads through his unclassifiable fiction.

Then The Only Good Indians hit the bestseller list last year, followed by glowing author profiles (including one by me) and lengthy reviews, eventually becoming the must-read horror novel of the year. He kept the momentum going with a novella, Night of the Mannequins.

Now Jones is back on the scene again, this time with My Heart Is a Chainsaw, an ambitious, heartfelt paean to the slasher flick with more meta-levels and twists than an Escher etching. Here’s my stab (sorry) at a plot synopsis: Jade Daniels is an impoverished, half-Blackfeet teenager in Prufrock, Idaho, a nowhere town on the shore of Indian Lake. When locals and tourists start dying, Jade, a veritable scholar of the Slasher film, sees the clawed hand of a local Freddy or Jason at work. She even identifies the town’s resident final girl, Letha Mondragon, a beautiful, virtuous classmate who lives in the upscale housing complex across the lake. As the bodies pile up, Jade finds herself trapped in the ultimate slasher flick.

The Veil spoke to Stephen Graham Jones from his home office in Boulder, Colorado, where he holds the Ivena Reilly Baldwin Endowed Chair Professor of English.

The Veil: Can you tell us how you got into horror when you were young?

Stephen Graham Jones: I started out reading westerns actually. I used to read a lot at my grandfather’s books and magazines, National Geographic and so forth, so one of my uncles noticed and he showed me his library, which was mostly paperback westerns. Louis L’Amour was a huge influence on me as a writer. My uncle also had Conan books. Living in a little town in West Texas, to be able to imagine a place like Hyperborea, it was so transportive. Then I read Tommyknockers when I was seventeen, and it blew my mind that a person could think like this. I’d been reading a lot of horror before that, all kinds of horror movie novelizations, especially every Friday the 13th I could find. To be in Jason’s head when he wasn’t killing people: that always fascinated me. But Stephen King was different. He’s my biggest influence. The thing I learned from him, and what I think a lot of us have learned, is that feeding a character that the reader doesn’t care about into the meat grinder doesn’t matter. The reader has to believe but not necessarily like that character. If the character isn’t real, the reader won’t care about them. The way to make the reader care is to give that character a real story. It’s good to hit the ground running in a horror story, with a big splash of blood even, but you have to slow down a little bit to let us know what matters to your character, which tells you what can be taken away from that character. What does that character have to lose?

The Veil: I know that you also love sci-fi, especially Philip K Dick. You’re a genre omnivore, so to speak, but you write almost exclusively in horror. Why has horror become your main dish?

SGJ: I love to write science fiction and fantasy as well, but I’ve realized that the science fiction and fantasy that I write, it always shifts gears into horror at some point in the story. My horror stories: they stay horror. I mean, no story is strictly one genre, they always carry traces of other genres, but with anything I write, I have a hard time from keeping the horror from taking over! That just tells me that horror is where I belong.

The Veil: Is it the same with your reading choices?

SGJ: I read a lot of horror, but I also read a lot of science fiction and fantasy, and I read a lot of paleoanthropology and literary fiction. I read all over the bookshelves because I feel that part of my job as a writer is to smuggle alien DNA into the field that I live in.

The Veil: So how did your love affair with the slasher flick begin?

SGJ: I was living in Wimberley, Texas, before Wimberley became a boutique arts community, when it was still a kind of junky place to live. I was in the eighth grade and I got to running with a group of kids, one of whom knew the clerk at the video store in town. If we went straight to the video store from school, that clerk would slip us six or seven slasher VHS tapes, and if we had them back by Monday morning, they didn’t have to be logged out. Which meant we got them for free. So we would go to a friend’s house, this kid who lived way out in the trees, and his dad had this junky garage with a ratty old couch and a nineteen-inch TV and a VCR. And we just watched those Freddy/Michael/Jason movies until one or two in the morning, at which point my friend’s dad would be deep enough into his six-pack that he would put on a Freddy glove and come scrape it on the metal door of the garage. We would just scream! We’d be trying to pretend we weren’t scared and grossed out by the movies, but we were terrified. So when his dad did his Freddy thing, we would just dive out the side door of the garage and run into the darkness outside. Somehow we came up with a rule that if we could make it to the creek and jump in, then we’d be safe. Which doesn’t actually make sense. That feeling of running terrified through the darkness as fast as I could while smiling so wide that my face hurt—to me, that’s the essential feeling of a Slasher. You never know whether you’re going to laugh or you’re going to scream. I think I just got addicted to that feeling right there and I’ve never looked away.

The Veil: Yes, I remember watching the first Friday the 13th at a rep theatre years ago, and no matter how often or how hard people laughed at the goofy bits, it did not take away from the screams during the scary bits. If anything, the laughs amplified the scares somehow.

SGJ: Oh, I agree. In horror, comedy acts as a pressure-release valve. It allows us to reset so that we can be set up better for the next time.

The Veil: In My Heart Is a Chainsaw, Jade writes a treatise on the slasher for one of her teacher. Do you agree with her analysis that the true first slasher flicks predate Halloween and Friday the 13th? She names Psycho (1960) and Peeping Tom (1960) as the granddaddies, then proclaims the giallo flick A Bay of Blood (1971) and Black Christmas (1974) as the first true slasher films. I mean, for me, the first and the best is still Black Christmas, which my brother and I use to watch on the local TV network every year in December.

SGJ: Oh yeah, Jade’s right about the lineage. And Black Christmas is a hell of a movie. That one’s by Bob Clarke, who went on to do Porky’s.

TV: He also did Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things, one of my favourite movies!

SGJ: And Death Dream, a really underrated picture. Black Christmas is definitely one of the first slashers and yes, it is just amazing. It has all the slasher elements right there, you know. But I think there’s a reason why Black Christmas didn’t codify the genre like Halloween, which really laid down the rules and gifted filmmakers with a formula that they could enact themselves. So why didn’t that happen with Black Christmas? It has so many of the same classic slasher elements. My suspicion is that Black Christmas didn’t catch fire not because, like some people argue, it was eclipsed by other films like Jaws and Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which came out around the same time. It’s because Jess Bradford, the movie’s final girl, who is probably a better model for a final girl than Laurie Stroud, doesn’t come into combat with the actual killer at the end of the movie. Not really. Jess goes up against her boyfriend, who she thinks is the killer, but there’s no battle with the real killer, Billy. That’s not a bad move, but I think if we were to see Halloween first—even though it came out later—and then watched Black Christmas, then Black Christmas would seem like a variation on the formula we all love. It’s like Black Christmas was offering a variation on a formula we didn’t know existed!

TV: It also might be a little too…real. Those phone calls, for instance, are just so believably creepy! I had a friend who used to crank call me in the voice of Billy, and it scared me shitless every time. That killer is also completely believable, and maybe not “archetypal” enough, like Jason or Freddy or Michael. It’s like there’s no release valve of fantasy in the film.

SGJ: Yes, Black Christmas and Halloween both have faceless killers, but they do it in different ways. We don’t really see Billy [from Black Christmas], except maybe for his foot going up a trellis, we only hear him. Then in Halloween, John Carpenter does that with a mask, and for some reason, I think the mask is more effective for the audience.

The Veil: What about Bay of Blood? I haven’t watched it since I was sixteen. Would you call that the first slasher?

SGJ: Well, like Jade says, it’s definitely the grandfather or step-grandfather of the slasher. It’s hard to trace a direct path of development for the slasher, but if you go all the way back to 1925 and The Phantom of the Opera, you have Lon Chaney as a masked killer or ‘threatener’, then you have the Scream Queens of the 30s, who are basically white women calling out in distress for help from men. Then in the 1960s and 70s, the giallo gave us a tight crew of people, like sorority sisters or people who work at the same place, and then you have a killer that is doing the point-of-view thing—we don’t look at his face, we look at his hands, we see what he sees. So that’s one way to trace the line. But most of those giallos have a serial killer, which is to say a gibbering madman killing for their own reasons, or the killings are done for greed, as in Bay of Blood, where everyone wants a piece of the valuable lakeshore land. You also had Psycho and Peeping Tom, and Herschel Gordon Louis in there with his grand guignol gore and Murder as Spectacle. So by the time you get to Black Christmas and Halloween, all these elements have snowballed together.

The Veil: My Heart Is a Chainsaw is not your first foray into the on-the-page slasher. I was wondering about the challenges of transposing the conventions and the scary fun of the slasher flick onto the page. The cinema slasher offers a whole language of scenarios and techniques that we know work because the audience screams when they’re supposed to. But I would imagine that’s a lot trickier with a novel. Is there anything that doesn’t translate onto the page?

SGJ: You’re right, the slasher grew up in the multiplex, so many of its conventions are seemingly locked into that space. With The Only Good Indians, to get that camera shot of the viewer looking through the killer’s eyes I had the killer herself do some of the narrating. I couldn’t do that trick again with Chainsaw because people would be expecting it. Now I didn’t consciously think this while I was writing, but with My Heart Is a Chainsaw I used the present tense to make it feel more cinematic. I think we experience movies more in the present tense; we’re dropped into the moment and we have to make sense of what’s going on. So I tried to capture that. Jump scares, though, are very hard to do on the page because the reader’s controlling the pace. It makes it very hard to surprise them. Now I have had people say that they experienced jump scares in My Heart Is a Chainsaw and maybe one day I’ll ask them where! And it’s funny, some of the stuff I’m reading online describes Jade as the narrator, but she’s actually a focal character and we’re looking over her shoulder. We’re so in her head that she feels like the narrator, and I think the present tense contributes to that. The first scene, with the Dutch kids, that one I told in cinematic conventions, like I did with Demon Theory (2006) and Zombie Bakeoff (2012), because Jade is seeing the killings on the phone that she finds by the lake. I included camera angles and things like that because it’s Jade’s version of what she’s looking at. When I got past that prologue, I had to strip that cinematic stuff away but keep the same feel—like Wes Craven was out in a boat thirty yards offshore! It was tricky, for sure.

The Veil: Jade is different from other characters in the genre because she wants to be in a slasher movie. She wants the bad thing to happen to her town that she’s practically almost willing it. Do you think that’s a common feeling for teenagers in her situation, outcasts, kids with shitty lives or no prospects? And do you think that’s part of the appeal of the slasher, the vicarious thrill of seeing the right people get killed?

SGJ: As terrible as it sounds, some of those characters on the screen seem to be asking for it. When you’re seventeen and you’re an outcast like Jade, your deepest engagement is going to be with a justice fantasy. She sees herself as powerless, so that she can’t get the justice that she feels the world owes her, from the town, from her school, from her family and her situation. Like she says in the book, she prays to Craven and Carpenter to send her a savage angel. Send her a Jason or Freddy to tip the scales of justice. She feels that what is most important is to get what is hers. She’s owed fairness and justice. However, wishing for one of those Michaels or Freddys to come to your town to dole out justice is one thing, living through it is another, as she finds out.

The Veil: Jade’s pick for her real-life final girl is Letha Mondragon: what were you trying to do with her as a character?

SGJ: Letha is Black, and like Jade says, in the typical slasher film the Black girl or woman is always “the friend,” the one who asks the real final girl if she’s all right and gives her a shoulder to cry on. I definitely wanted to go after that. I wanted to have Letha front and centre. She really has no flaws, except maybe that she cares too much.

The Veil: She does have a crappy family.

SGJ: Yes, but a good situation. In The Only Good Indians I wanted to play with the idea that a final girl could win without having to cash in her identity, that she wouldn’t have to adopt traditionally male characteristics like muscles and fighting ability to win the day. She could use compassion to win. In My Heart Is a Chainsaw, I was trying to question how the final girl has become such a trope, so idealized, that normal people on the street think that identity is unattainable. That’s how Jade feels, that she could never fit into that mold of the final girl. She doesn’t fit the body lines, the history, all that. But the final girl should be there as a model for all of us to fight back against bullies. If the final girl becomes too much of an ideal, we’re not able to adopt that identity to resist the bullies in our own lives. I wanted Letha to be that super-idealized girl, but then have someone else, who’s not a traditional final girl, step in and be the real heroine. I mean, being a final girl is not who you are on the outside, it’s who you are on the inside, what you carry. If I could have a thesis for My Heart Is a Chainsaw, I would want it to be that.

The Veil: In looking through your work, I noticed that you often tell your stories through the eyes of young people, teenagers. Do you find it easy to access that voice?

SGJ: Yeah, I wonder sometimes, Did I never grow up? Why do I write about teenagers so much? I haven’t figured that out yet. I was talking to someone a while back and I realized that was is so compelling to me about being sixteen or seventeen is that when you’re that age and you look back to when you were ten or even five, you realize that you were a different person. But when you’re sixteen or seventeen, you feel like you’re finalized, like this is my final form. And these ideals that I hold to so fervently are going to be the ideals I hold for the rest of my life. Of course they’re not—by the time you’re twenty-six, you’ve made so many compromises that you’re a completely different person. And that is what it is—it’s not bad, but that’s just what happens. So I just love to go back to that feeling of, This is who I’m going to be forever.

The Veil: Okay, I feel like I have to ask this to satisfy my curiosity: What is your favourite slasher and why?

SGJ: Scream, and the reason I love it is—well, for one thing, it doesn’t exploit women. So many slasher films, especially from the Golden Age, it feels like the casting agent stood at the bus stop waiting for naive girls to arrive from Iowa so he could offer them a part as a victim. It just feels sleazy. With Scream, a lot of the talent was pulled from TV, which set a different tone—these actors had more control over their careers and their roles and it shows. I mean, you also had Drew Barrymore, who is the Janet Leigh of Scream: you think she’s going to carry the whole movie, and then she dies in the opening scene. But what I like most about Scream is that it sends up the genre but it also enacts it as well as anything that’s been done. It’s scary and keeps you guessing. If you’re watching it for the first time, you think, It can’t be the boyfriend, but you never guess it could be two people doing the killing. As I say in the acknowledgments [of My Heart Is a Chainsaw], a friend took me to see Scream in 1996 and I came back to the theatre for the next six nights in a row. So ever since ’96, I’ve been watching Scream and reading articles on it and reading the screenplay. I feel like I live inside that movie as much as anyone. Someday I’d love to sit down with Kevin Williamson, though I’d probably just sit there like an idiot and not say anything.

The Veil: I don’t think most directors could have pulled off that script, though. Without Wes Craven, it probably would have come off as an occasionally scary, cute meta-comedy.

SGJ: I agree. There’s never been a director whose better in a tight hallway than Wes Craven. He understands the angles and composition of fear, the staging of it. You feel what’s happening even in the corner of the screen.

The Veil: Is he your favourite director?

SGJ: Yeah, for sure.

TV: Well, that was my final question. From all of us, thanks for the interview and thanks especially for all the books.

SGJ: You’re very welcome.

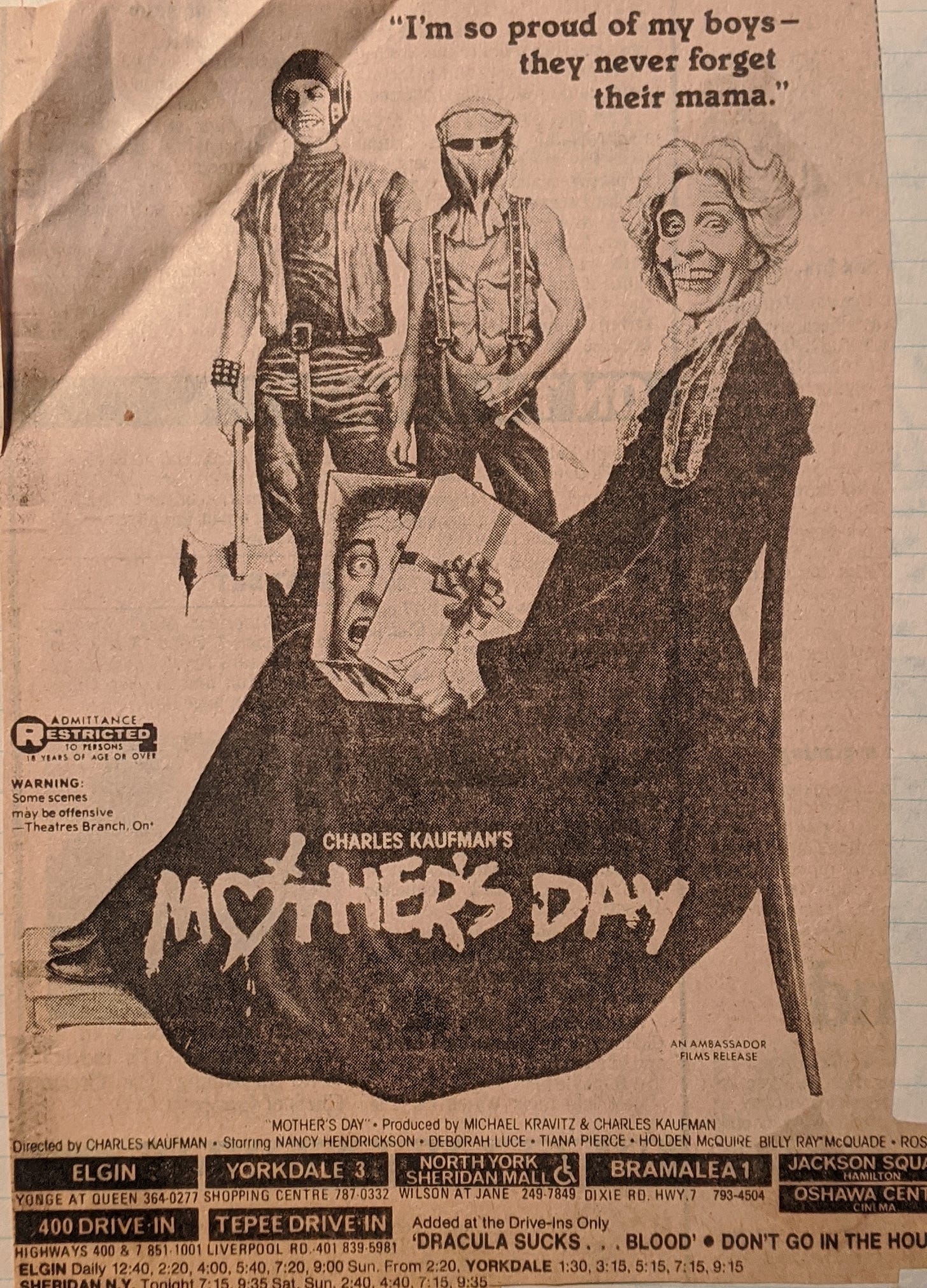

(Author photo by Gary Isaacs and My Heart Is a Chainsaw cover image courtesy of Simon & Schuster. Slasher movie clippings are from my horror-nerd scrapbook, circa 1981.)

Very interesting interview, James. I also really like the artwork. Now I want to read both of SGJ's latest books. Thanks for shating this.

Testing, testing, 1-2-3...