A Pig’s Heart

“Did Ted tell you what it looked like?” I asked Chris. “The…thing that was floating beside him? How did he know it was real?” The idea of an abused child’s spirit or astral body torn from its moorings by sexual abuse so shocked my sense of fairness that I peppered Chris with questions. Why didn’t Ted tell his parents about the abuse? With all of his money and power, why hadn’t he tracked down the abuser? And why didn’t he share his story with the millions of abuse survivors around the world, or set up a foundation to help sexually abused children?

As Chris soon made clear, I might as well have asked why Adam and Eve broke the one rule laid down in the Garden of Eden. Without saying it directly, Ted was sharing not only his own Origin Story but a parable about evil itself. Or at least that’s how he wanted Chris to interpret it—or how Chris wanted me to. Was Ted imposing a metaphysical truth on the story or was Chris? My answer changes depending on my mood. Maybe that’s why I’m writing all this down, to put another degree of separation between myself and those questions.

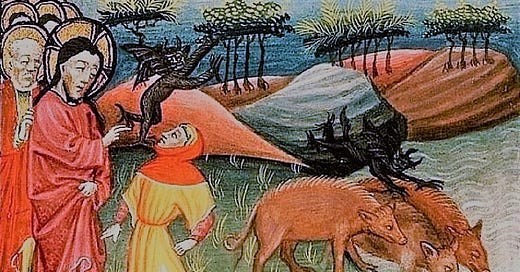

Chris waited for me to blow off as much steam as I needed to, then he started again. The entity—which Ted called a daemon, with an a, a distinction I found horribly pretentious—had a substance and shape but not what we would consider a body. Ted compared it to a virus, which borrows its outward structure from its host. So for Ted at age six, the daemon appeared as a cross between a miniature monkey and a cat, with a distinctly human but doll-like face. If Ted had been an adolescent, the daemon might have assumed a more alluring human form, a projection of masculine power or even sexual potency, but the childlike blend of cat, monkey and clownish mannequin was the ideal form to put a child’s mind at ease.

The daemon, which Ted came to know as Peabody, greeted Ted in its vibrational language, calling him friend, as if they were old pals. He said, This is a good place, in a tone that reminded Ted of a children’s TV host reading from a picture book. Yes, it is a good place, Ted agreed, a wonderful place. That’s when Peabody promised to teach Ted to speak without talking, to hear without ears, and to travel far beyond the walls of that scrubbed, squalid home, even beyond the very limits of this world. Was Ted ready to learn? Peabody asked. Of course he was.

So began lesson one. Did you know, friend, Peabody began, that you have more power here, in this place, than you do down there? Peabody was referring to the world that Ted’s physical body inhabited, a world that Ted sensed was contained within the “floating world” as he called it. The two worlds were separate, Peabody explained, catching the trail of Ted’s thoughts, but they also overlapped and intermingled, a little like oil and water inside a bottle. Down there, you are just another body, weak, defenseless, Peabody said. Here you can be as powerful as a giant.

Ted was confused. How could he, a spirit as light as the wind, be stronger than his flesh-and-bones body? He may not be the biggest or fastest boy at school, but his body could carry a bag of potatoes from the grocery store to the car and throw a ball hard enough to break a window. As far as he could tell, his spirit body wasn’t even strong enough to turn the pages of a book. Ted wondered what his astral body was actually for. Without flesh and bone and blood to anchor his feelings, life in the floating world attained a film’s focused intensity, every event signifying without personally involving him.

“Ted tried to describe astral travel to me a few more times before he gave up,” Chris said. “I was still waiting for the story to lead back to the package I’d delivered, which sat there on the table where Ted had placed it. I couldn’t chuck the feeling that the bag was slowly lowering the temperature in the room. That was impossible: all the windows and the glass doors were open to catch the tropical breezes rolling up the beach, but it felt like the AC was kicking in. It was beyond weird.”

I knew what Chris getting at. Not only was I desperate to know how the story’s disparate parts fit together, the room where Chris and I sat was also in the thrall of an unexplainable atmospheric disturbance. If I relaxed my attention even for a moment, my senses glammed onto an alien presence somewhere in the back of the apartment. It took everything I had to ignore the threat. The cats noticed. Not one of them was napping.

“Peabody told Ted that he would teach him how to awaken his powers. Right now it it was almost time for Ted to return to his vessel, the word Peabody used to describe the physical body. Your vessel is a tool to use as you see fit, he told Ted. Remember: you are not your vessel, just a pilot is not the airplane he flies. You are the master. You command your vessel, and you protect it from your enemies. Ted knew his enemy’s identity: the fucker was sitting in that arm chair violating Ted’s vessel.”

Chris grabbed the notebook and tore out a blank page. On it he drew a Medieval sigil of a type familiar to me from black magic manuals and treatises, a large circle containing five curving lines that framed a single Aramaic letter, which I won’t share here.

“Peabody drew this sigil in the air with a long, spider-like finger and told Ted to remember it. He also gave Ted three words to remember, followed by a short but specific set of instructions. When you return to your vessel, he said, write down what you’ve heard and seen. Follow my plan, and your enemies will fear you.”

I gripped the chair’s armrests, forcing myself to stay seated. I owed it to Chris to hear him out and help any way I could. And let’s be honest: I couldn’t leave without hearing what happened next.

“Ted returned to his body made it the play room without forgetting Peabody’s instructions. He drew the sigil and wrote down the three magic words, but he was smart enough not to put the plan itself to paper. He mustn’t leave behind any evidence.”

That weekend, as per Peabody’s plan, Ted went with his mother to the grocery store. Because this was the 1970s, it wasn’t unusual for a kid to wander away from his parents in a store, and this Ted did, slipping from his mother’s side when spotted his target: the meat section. Peabody had been very clear: Go to the meat section, and go alone.

The area was huge, but Ted soon found the fridge he was looking for. In those days, organ meats were still de rigueur on family meal plans, and there in the display case, set among the livers and kidneys and tripe coils and brains, Ted saw it: a pig heart. Peabody had been very specific on this point. Not a cow’s brain or a sheep’s liver but an actual heart from an actual pig. And don’t ask your mother to buy it, Peabody said. She will think you have gone mad. Steal the heart. There is no other way.

Ted stood in the aisle holding a pig heart wrapped in cellophane, a six-year-old kid stunned by indecision. He’d never stolen anything before, and his parents had taught him not to lie, especially to adults. But there was no other way to procure the heart, and the heart was essential to Peabody’s plan. One side had to win. Would it be the goody-good boy desperate for his mother’s approval, or this new boy, who wanted nothing less than to command his own body like an old-time sea captain piloting a ship to unexplored waters?

There match didn’t last long. Ted had worn his thickest winter coat—again, as per Peabody’s instructions. He made sure no one was watching him and then slipped the wrapped pig heart inside his coat, pressing it close to his own heart before he pulled up the zipper. Then he rejoined his mother and left the store with her, his crime undetected.

“Ted was surprised at how smoothly it went,” Chris said. “Not just the theft but how he easily he overcame his reservations. He didn’t know it yet, but his journeys on the astral plane had strengthened his spirit, giving it a tougher skin. In the supermarket and in the car on the way home, Ted could still feel the fear and guilt roiling through his body, but they were more like sensations than actual emotions. If he focused on those feelings, they had no more power over his mood than a sneeze or a twitching eyelid. They could be ignored if he chose to. The lower emotions are merely of the body—that’s how Peabody put it, and Ted said he was right.”

The next step of Peabody’s plan was easier. When he got home, Ted took the pig heart to his room and drew the sigil Peabody had shown him on the flesh with a magic marker. He rewrapped the heart and hid it in the garden shed, where the cold kept it fresh. Before leaving for school on Monday morning, he put the heart in a brown lunch bag and transferred it placed to the back of his school cubby hole. After he arrived at the babysitter’s house, Ted waited for one of the kids to call the mom away from the kitchen. When she finally left the room, he got the heart from his school bag. It was time to act.

Ted snuck into the living room with his package and eased the doors shut behind him. The room was almost dark but he easily found his way to the arm chair. He took out the pig heart and tore off the cellophane. Then he slipped the heart under the babysitter’s chair and left the room.

“What happened?”

“Nothing,” Chris replied. “Not for the first couple of days. The dad worked late Monday and got so pissed Tuesday he went straight to bed. On Wednesday he came home early. He took his time grooming the kids before he summoned Ted to the living room with him. It was the usual routine. The man put on “Waterloo” and sat on his favourite arm chair, and lifted Ted on his lap. Before the first chorus played, Ted was out of his body and looking down from the ceiling at the babysitter. There was no sign of Peabody. As far as Ted knew, his spirit was up there alone.”

Then something happened. An invisible ripple disturbed the aether, a pulse that did not quite rise to the level of sound. This pulse, which repeated three times, seemed to emanate from the arm chair—No, Ted thought, not from the chair but underneath it. From the pig’s heart. The babysitter sensed it too. He was reaching for his zipper when his body lurched forward as if the car he was riding in had been rear-ended. He sat up straight and scanned the gloom for almost a full minute, using Ted’s body as a shield before he eased back against the chair and sat there stunned, his eyes squinting, lips curled into a grimace, the boy forgotten on his lap. He was terrified.

Ted’s job was finished. He returned to his body and slipped off the man’s lap, his nose catching the slightest sweet whiff of raw meat on his way to the French doors. He never entered the living room again. As Ted learned much later, the babysitter never left the room. Ever.

The next day when Ted arrived at the babysitter’s house he overheard the mother talking on the phone. She was telling a friend that her husband hadn’t gone to work that morning—he hadn’t even left the living room since yesterday. Ted peeked into the room. He could see the man’s profile in silhouette. He was leaning forward in the chair, wringing his hands and running them through his hair, whispering to himself, letting out little gasps and squeaks. The stereo was turned low, but Ted heard the familiar lyrics, “Where will you meet your Waterloo…”

The day after that, a Friday, the children were barred from the kitchen. The mother spent an hour on the phone, fighting to keep her voice under control. On Sunday, Ted’s mother told him he’d be going to a new babysitter on school days. She didn’t say why. The next evening, a small caravan of police cars and ambulances and fire trucks pulled up to the babysitter’s house. One ambulance took the father’s body to the morgue. Another raced to the hospital with the mother. The family left the neighbourhood a week later.

“It took a lot of digging and bribery, but thirty years later, Ted—all grown up and richer than a Pharaoh—Ted got his hands on the coroner’s record. He showed me a copy. Had it in a file at the table.”

I lacked the character to tell Chris to stop. What possible good could come from learning how the babysitter died? Why trade a few moments of ghoulish satisfaction for a horrifying picture that might lodge in my mind for the rest of my life?

“The man who molested Ted had holed himself up in the living room for five days. He wouldn’t even leave to use the bathroom.” Chris hugged his arms close to his body. “The wife begged him to come out. She begged, she pleaded, she yelled at him, but he stayed there in his favourite arm chair, mumbling and crying and pleading to someone only he could see or hear. The smell of rotting meat finally drove the wife to call the police. It was too late. The cops found him sitting in the arm chair. He appeared to have suffocated. At the hospital, the coroner found a large object lodged in his throat, so large they couldn’t figure out how he could have swallowed it so deeply.”

I was already groaning.

“It was the rotting pig’s heart. The poor fucker had swallowed it whole.”

The next installation of The Heart of a Pig, “The Pagad Sheirim,” will appear next week. To read Part I, click here; to read Part II, here; Part III is here, Part IV is here and Part V here. Keep the comments coming, and if you like the story, please take a moment to share the joy on your social media channels.

I knew what Chris getting at. / Their match didn’t last long. / and transferred it placed to /

A few more you might wish to modify.

Eeeeeeew, yuck. I noted quite a number of errors. Hope you don't mind my picky proofreading. First one: Why didn’t Ted didn’t. I believe there are several more (wish I'd copied and pasted as I read), but I'm too lazy to read it all over again. Look forward to the final installment.