The argument has often been made that horror fiction, with its emphasis on achieving a unified effect—that is, to frighten the reader—is best suited to the short story form. The evidence for this position rests on two points.

The first is straightforward: the atmosphere of dread and awe that accumulates in horror fiction is dissipated soon after the reader puts down the book. Therefore, any horror tale that can be read in one sitting is more likely to achieve its aims than a novel, which must be read over the course of days or weeks.

The second point rests on HP Lovecraft’s observation that terror—the apprehension and anticipation of the horrible—is more powerful, as an emotion and storytelling technique, then horror itself. According to this definition, the monster we imagine behind the closet door is always more frightening than the monster we see when the door opens. The monster’s long-apprehended appearance evokes revulsion and fear, but also a kind of catharsis, even relief—with the object of our terror finally revealed confirmed, we are free to choose a course of action. Everything that follows the reveal is pure denouement, with the final girl or paranormal investigator pitting their will and fighting skills against the monster’s. Given this dynamic, Lovecraft contends, the short story is generally superior to the novel.

It’s true that the best short horror fiction achieves a purity of effect and intensity of feeling unmatched by any novel. The form’s frustrating restrictions and aesthetic demands also tend to attract an exacting, obsessive sensibility—the true weirdos of horror are the short story writers—more likely to produce work of the highest literary quality. But what the short story gains in one effect, it loses in another: the feeling of immersion. Horror novels offer an entire realized world, where characters and subplots and ideas flourish and diminish until the monster, fully manifest and multitudinous, is laid to rest.

The Veil has no pony in this race. Greatness is rare and not confined to genre or format. For today, let us consider ten great short horror stories. Anyone familiar with the stories below will note that only one (Robert Aickman’s “The Inner Room”) was written within the lifespan of any but the most elderly reader.1 Why are there no contemporary stories? Not from a lack of quality stories. There are simply too many stories written in the last fifty years to make a meaningful assessment at this point. With older works, time has already performed the necessary (and not always fair) sifting of wheat from chaff, narrowing the field of choice to a manageable number.

So here, in no particular order, is The Veil’s Top Ten horror stories.

The Willows, Algernon Blackwood: In his rambling treatise Supernatural Horror in Literature, HP Lovecraft named Blackwood’s “The Willows” the best supernatural tale in the English language. Like all authors who dabble in literary theory, Lovecraft was making a case for the fiction he loved and composed, tales that emphasize terror over horror, atmosphere over plot, tales of cosmic horror over ghost stories. Pet theories aside, Lovecraft recognized a great horror story when he read one. “The Willows” mutates from an almost romantic rumination on the pleasures of travel and nature into a shocking encounter with an alien presence that possesses a sandbar of willow trees on the Danube.2 One of the foundational texts of cosmic horror.

The White People, Arthur Machen: Not a prequel to Get Out but Lovecraft’s second-favourite work of supernatural fiction. Fans as varied as Guillermo del Toro and Stephen King have also rhapsodized about Machen’s sinister novella, citing its hypnotic power and unbearable suggestiveness. Machen employs a Conradian framing structure in which two erudite men, settled in for an evening of brandy and cigars, discuss a strange journal—the Green Book—discovered by one of the men. The Green Book, which forms the long middle section of “The White People,” recounts a young girl’s initiation into a witch cult and the visionary powers bestowed upon her by the cult’s rituals. The men’s philosophical discussions about the journal, which analyze but fail to explain its meaning, matches the reader’s own experience. What did we just read? Is it as terrible as our senses suggest, and what does the events and entities it describes say about evil and goodness?

The Sandman, ETA Hoffman: In his frustrated efforts to describe the uncanny, Sigmund Freud listed several objects likely to trigger an “uncanny” sensation: waxworks, prostheses, glass eyes, doubles, mechanical devices that appear human. Although seemingly ordinary, these objects, when freed of our customary associations, are revealed as sly violators of the natural order, the equivalent of a corpse sitting up on its hospital gurney to request a glass of water. Expounding on his thesis, Freud wrote an in-depth analysis of ETA Hoffmann’s 1817 story “The Sandman.” What’s the story about? A typically idealistic German student, who as a child witnessed his father’s participation in a sinister alchemical experiment, falls in love with a professor’s robot-like doll. And the story’s effect? A jolt of skin-crawling uncanniness likely followed by a rush of sensations and desires best discussed with your therapist. A truly original work of the imagination.

The Monkey’s Paw, WW Jacobs: The story that launched a thousand “Gotcha!” endings, “The Monkey’s Paw” is so solidly constructed you feel like you can reach into the page and pull out the story whole, so that the story itself feels as much a singularly cursed artefact as the monkey’s paw it describes.

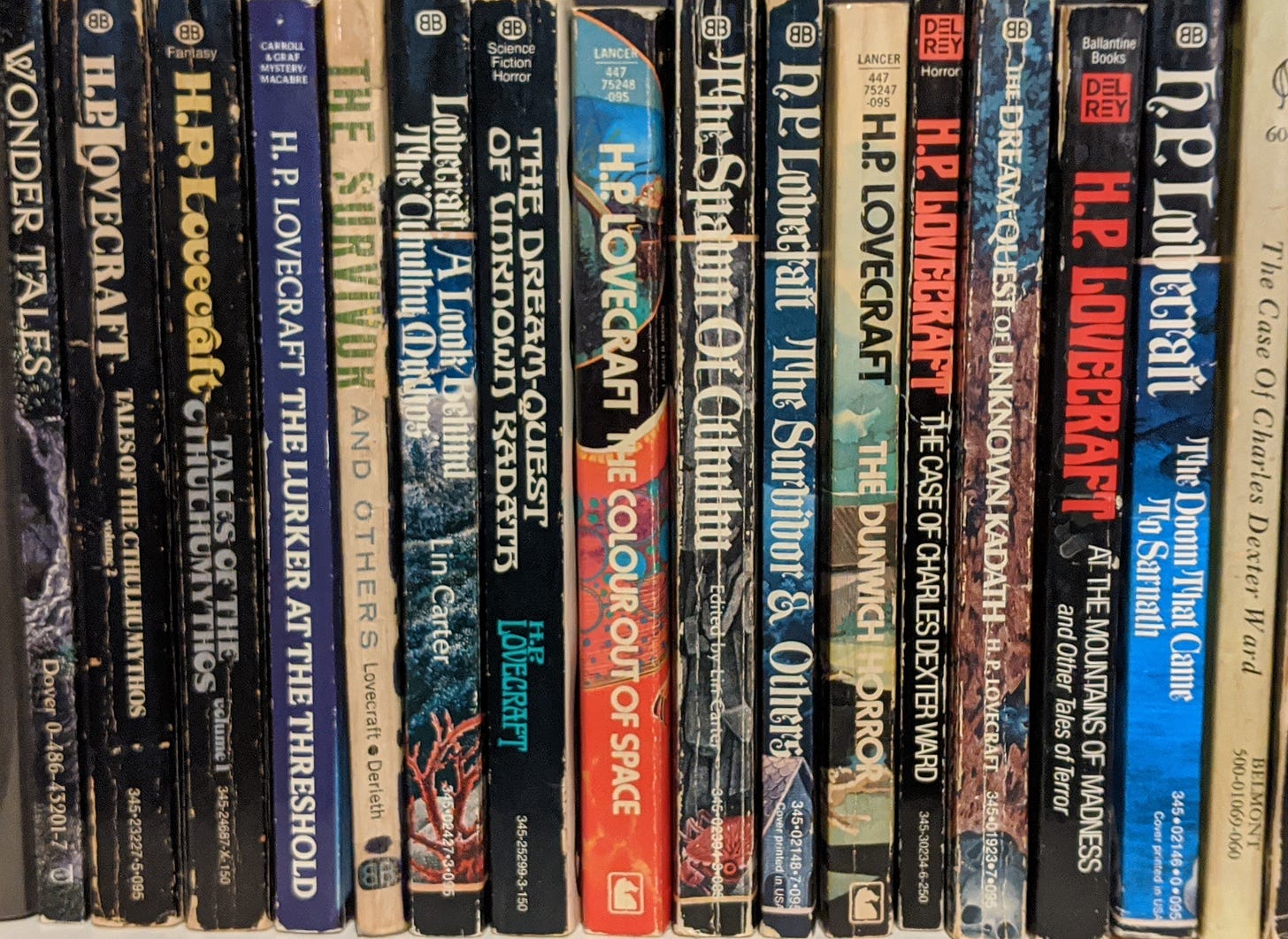

The Colour Out of Space, HP Lovecraft: The Night Gaunt of Providence’s reputation largely rests on his invention of a detailed cosmology of pan-dimensional deities and creatures (in this way, he is horror’s Tolkien). True enough, but Lovecraft is also singular in his ability to describe the weird, which writer Mark Fisher defines as “that which does not belong.” When we encounter the weird, we recoil and say, “What I’m seeing can’t be true. Maybe in outer space, maybe in Hell, but not here.” In “The Colour Out of Space,” Lovecraft brings his gifts to describing a colour that does not exist. The threadbare story and characters—the conventional detective-story construction, the snobbish protagonist and the cornpone yokels he’s investigating, the hideous transformation of the landscape—are like the filigree mounting that holds a rare jewel in place, efficiently crafted but eclipsed by the jewel’s alluring otherworldliness. Lovecraft makes you see the unimaginable colour, if only for a moment, in your peripheral vision, but it’s there and you can’t un-see it.

The Horla, Guy de Maupassant: The great Naturalist author tried to slit his own throat a few years after he wrote “The Horla.” The two events may be related. (Maupassant was actually entering the late stages of syphilis-inspired insanity when he conceived of the story.) “The Horla” is told in diary form. The narrator, a bourgeois bachelor, waves at a passing ship, an impulsive action that invites into his home, then his mind, a malignant alien entity that lives entirely on milk and water. Maupassant’s tale is all the more terrifying for the sober, convincing details he brings to the man’s total possession by the Horla, which make you believe that “milk and water” is exactly what a Horla would live on.3

The Lottery, Shirley Jackson: “The Lottery” might have been written to illustrate anthropologist Rene Girard’s observation that social cohesion is most effectively achieved and maintained by ritualized scapegoating. Any gifted writer could have conceived of the plot—a small town chooses, via a crude lottery, one citizen to be stoned to death in an annual ceremony—but only Jackson could have made the protagonist, a seemingly harmless busybody, so familiar to the reader’s own sensibilities and prejudices. That familiarity so shocked readers that The New Yorker, which first published the story in 1948, was deluged with hate mail. Given how many good citizens are taking to the digital airwaves these days to stone their neighbours and ideological enemies, “The Lottery,” which insists that we are not be the good guys we imagine ourselves to be, deserves another reading.

Green Tea, Sheridan LeFanu: Like all good fiction, horror tales expand beyond mere emotional and psychological effects into the realm of allegory. In this story of a mentally disturbed gentleman haunted by a monkey with glowing red eyes, Sheridan LeFanu, who, along with Poe, pioneered the post-Victorian horror story4, found the perfect allegory for mental illness. A gloomy obsessive man whose wife likely committed suicide after a long struggle with depression, LeFanu knew mental illness and anguish from the inside out. In “Green Tea,” he symbolizes depression into the form of a demonic monkey, tireless in its efforts to bring low its host, then dramatizes the futility of rationalist approaches to mental illness. Anyone whose ever been told to “think about something else” or “relax” when suffering from depression and anxiety will feel for LeFanu’s doomed patient.

The Black Cat, Edgar Allan Poe: Poe’s best short stories are probably the closest that any English-language author has come to approximating the formal structure and exacting language of poetry in the prose format.5 “The Black Cat” may be the best of Poe’s tales, one of a handful that profoundly influenced future generations of horror, suspense and mystery authors, as well as the French Symbolists, the Decadents, the Modernists, the Surrealists, and just about every other avant garde movement of the 19th and 20th centuries.6

The Inner Room, Robert Aickman: The fiction of Robert Aickman invites descriptive cliches of a higher literary order than The Veil can pull off at on such a demanding schedule. To read Aickman’s unclassifiable stories is to enter a dream world in which we are constantly reminded that dreams so fully absorb our attention because their skewed premises and dislocations are so persuasive, at least while they unfold. Like the most fantastic dreams, Aickman’s stories are constructed from the grubby details and discomforts—a pair of pinching shoes, a frayed cuff, an embarrassing social gaffe—that constitute so much of waking life. In “The Inner Room,” a young girl whose birthday outing is ruined by bad weather is gifted a dollhouse and a family of dolls by her parents. Years later, the doll house is thrown away, and many years after that the now grown-up girl is stranded in a life-sized version of the same doll house. And she’s not alone.

You may also notice that four out of the ten stories reference colours. Make of that what you will.

T Kingfisher spun a highly enjoyable novel of cosmic horror from Blackwood’s premise, The Hollow Places (2020).

Lovecraft cited “The Horla” as the inspiration for “The Call of Cthulhu.”

That LeFanu and Poe, who were born five years apart, pointed the way forward for the conventional Victorian/Gothic horror tale while living through the height of the Victorian era is all the more remarkable.

This is probably why Poe’s only completed novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, never really gets off the ground.

Dostoevsky also acknowledged his debt in an introduction he wrote to a Russian translation of Poe’s work.

Thank you for this post. I just ordered the Oliver Onions collection, despite the warnings of reviewers on Amazon, as well as a Leonora Carrington collection. I really enjoy your blog.