It is a testament to the impact of Stephen King’s work that The Veil has not interviewed a single author who didn’t name King as a major influence on their work and their discovery of the horror genre. This trend is bound to continue. If you were born after the Baby Boom and got into horror when you were young, then you probably lost a few adolescent summers to King’s gaggle of killer clowns, rabid dogs, small-town monsters and high-school freaks.

So what is the appeal of King’s fiction? There’s the uncanny storytelling skill and the sheer imaginative reach and scale of the best work. King is also an unabashed Fan Boy of not only horror but every pulp genre ever sold on a drugstore book rack. His knowledge and understanding of genre fiction is such that, if King had chosen to write detective novels, spy thrillers or space operas, he’d probably still have been the most popular author of his generation. King knows what details are important to the story and to each characters’ development, and he knows how to lay them out in the proper order and at the proper time. If only it were as easy as it sounds.

Those gifts don’t quite explain the passion and loyalty of King’s legion of Constant Readers. Maybe because those readers are largely horror fans, not enough attention is paid to the fact that King’s monsters and victims are the polar stars of an unabashedly sentimental worldview. King gushes over his favourite characters, and he despises bullies, cruel parents and corrupt authority figures more than any author since Charles Dickens. King remembers what it feels like to be a child, alone in the dark staring at the bedroom closet door, and he is experienced enough to know that the boogeyman behind the door is not half as scary as what’s waiting beyond the bedroom door. Readers will never get enough of that.

No appreciation of King’s work would be complete without a Top Ten List, but to keep the list manageable, The Veil editorial team is confining its deep thoughts to the novel-length works.

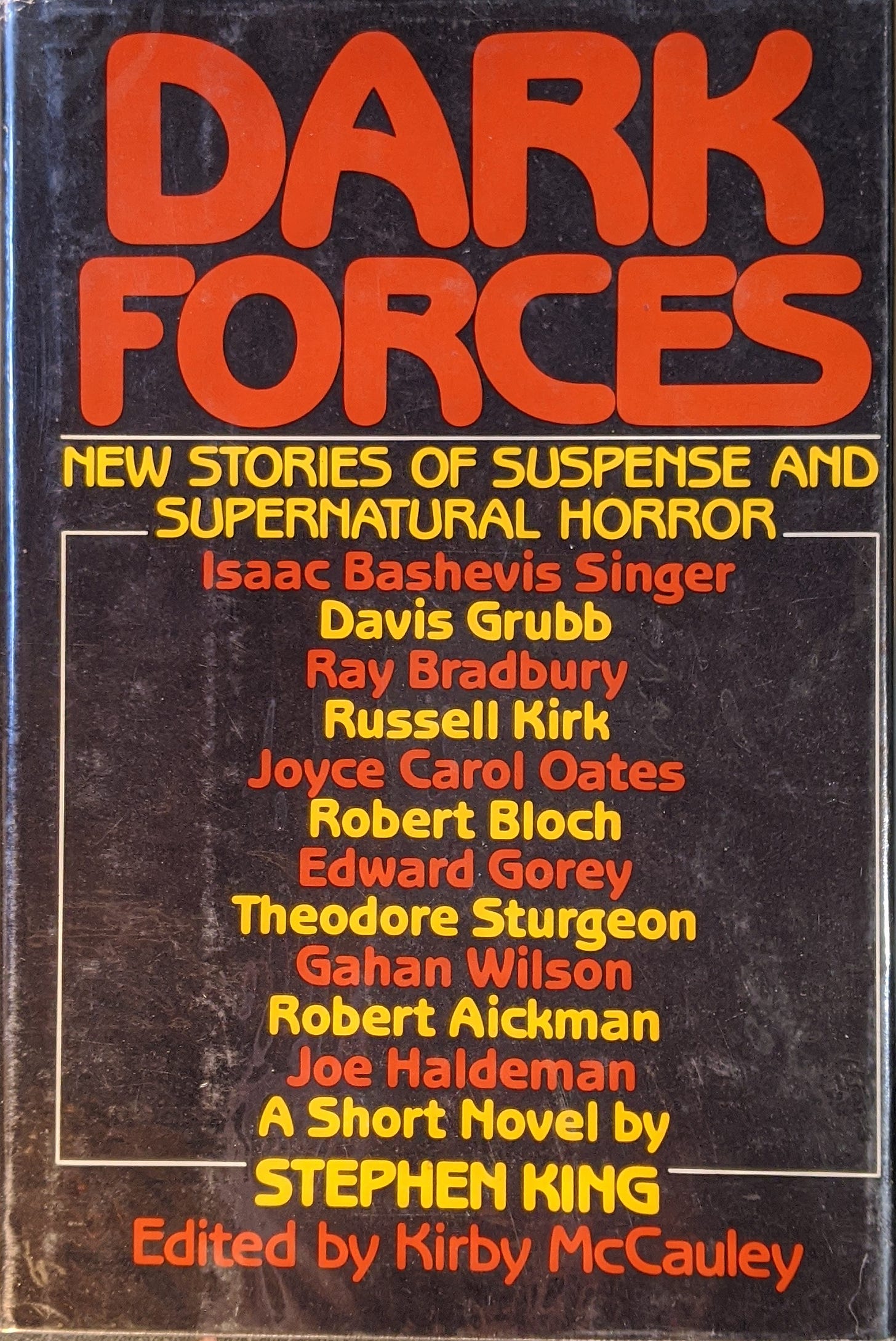

10 The Mist (1980): Rocking more tentacles and bulging bug eyes than a Cthulhu plush toy convention, The Mist first appeared in Kirby McCauley’s somewhat highbrow anthology, Dark Forces. The short novel is propelled by the storytelling economy of an early morning nightmare and peopled by characters whose brutish religious atavism would make them feel at home in a Shirley Jackson or Nathanial Hawthorne story. An absolute joy to read in a single sitting.

9 Hearts in Atlantis (1999): Okay, this is a collection of novellas and short stories, but they are linked by enough recurring characters and themes to constitute an unconventional novel. Hearts in Atlantis, along with Bag of Bones, also signals the end of King’s extended slump, that run of sloppy, poorly edited doorstoppers that began around 1986 with the publication of It1, when King’s struggle with alcoholism and drug addiction started to take a toll on his work. The long opening novella, “Low Men in Yellow Coats,” features King’s most nuanced and moving depiction of a deprived childhood, nuanced because the primary victims in this story are the adult caretakers not the children (though they get slapped around by life, too).

8 11/22/63 (2011): Any author can come up with a compelling “What if” storyline; Stephen King may be alone in his ability to charm an effortlessly readable 850-page time-travel epic from one. If the novel’s titular date doesn’t give it away, the “What if” of 11/22/63 would be, “What if you could go back in time and prevent the assassination of John F Kennedy? Would you do it?” Through a freak time-space anomaly, schoolteacher Jake Epping is given such an opportunity and reluctantly assents, a choice he later regrets. King’s conception of the whys and wherefores of time travel is eerily believable and concrete, as is his recreation of early-1960s America.

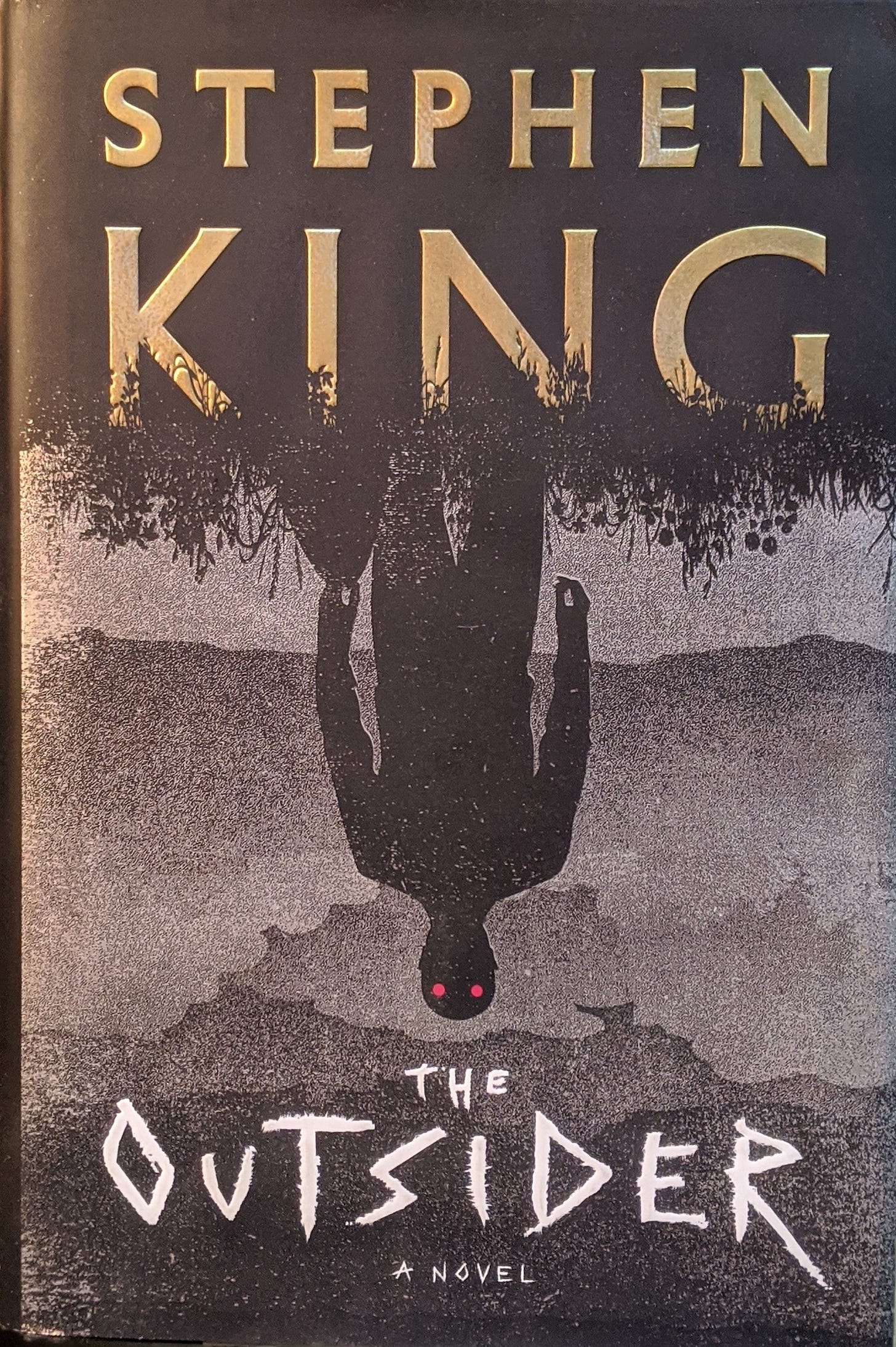

7 The Outsider (2018): King brings back Holly Gibney, his most fully realized female character, for a solo outing about a shape-shifting serial killer. Gibney, an OCD-suffering private eye schooled by curmudgeonly Bill Hodges of the Mr Mercedes trilogy, is brought in to help when an accused child murderer is caught on video both at the scene of the crime and at a conference hundreds of miles away. The Outsider is King’s most enjoyable genre mashup, combining elements of the closed-room mystery with the contemporary police procedural, the serial-killer thriller, and the cosmic horror tale.

6 The Dead Zone (1979): Now that Donald Trump is out of the Oval Office we can all go back to appreciating The Dead Zone for more than its (supposedly) prescient depiction of a Republican President Gone Wild. The simple plot line is familiar by now: John Smith, an archetypically ordinary man, emerges from a five-year coma burdened with an extraordinary gift, the ability to see into the future. That gift draws him into whirlpool of impossible moral choices that make him wish he’d stayed asleep. King channels the American High Gothic atmosphere of sin and fate while ratcheting up the suspense with every unwanted vision into the future.

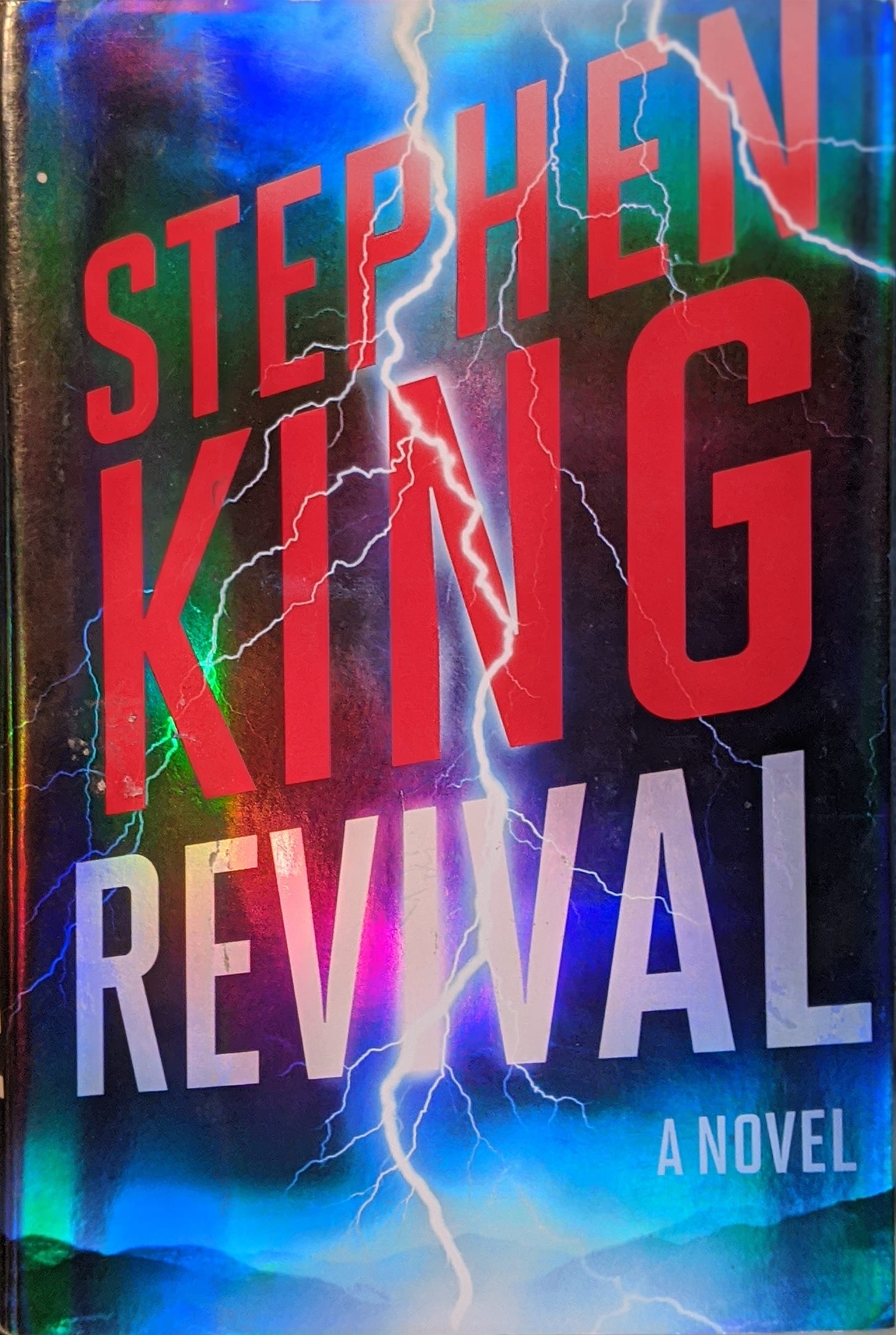

5 Revival (2014): King has always been generous in his praise for those authors dead and living who’ve influenced his work, and his fiction is threaded with allusions to Poe, Lovecraft, Arthur Machen, Shirley Jackson, Ray Bradbury and other genre masters.2 In Revival, King’s second scariest novel, he channels Lovecraft’s greatest opening line—“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents”—into a relentlessly dark story of two men who choose to forgo this mercy. The climax is so unhinged you can almost hear King cackling to beat the Crypt Keeper as one character after another goes mad and white-haired from the horror of it all.

4 Salem’s Lot (1975): When Salem’s Lot, King’s follow-up to his debut novel Carrie, was published in 1975, uppity critics dubbed it, “Peyton’s Place meets Dracula.” That description has stood the test of time, though not in the sneering manner intended. Salem’s Lot is an audacious re-imagining of Stoker’s novel, stripped of its high Victorian cadences but none of its majesty and reset in a grubbily common American small town.3 Probably the most influential of the now classic 1970s horror novels—along with Rosemary’s Baby, Carrie, The Exorcist and The Other—that launched the paperback explosion of the 80s. (The Veil is aware that Rosemary’s Baby was published in 1968, but the novel is the uncanny love child of the bleak 1970s.)

3 The Shining (1977): Having taken a shot at the iconic vampire tale in Salem’s Lot, King turned his attention to the haunted house story with The Shining. In King’s telling, and even more so in Kubrick’s film version, the glamorous Overlook Hotel stands in for America’s blood-soaked history of colonialism and exploitation, with alcoholic caretaker Jack Torrence playing the role of lumpen proletariat. King never lets the novel drift into ideological abstraction, keeping the story’s injustices and abuses and frights close to Jack and his abused family’s bones. Also: a great haunted house novel.

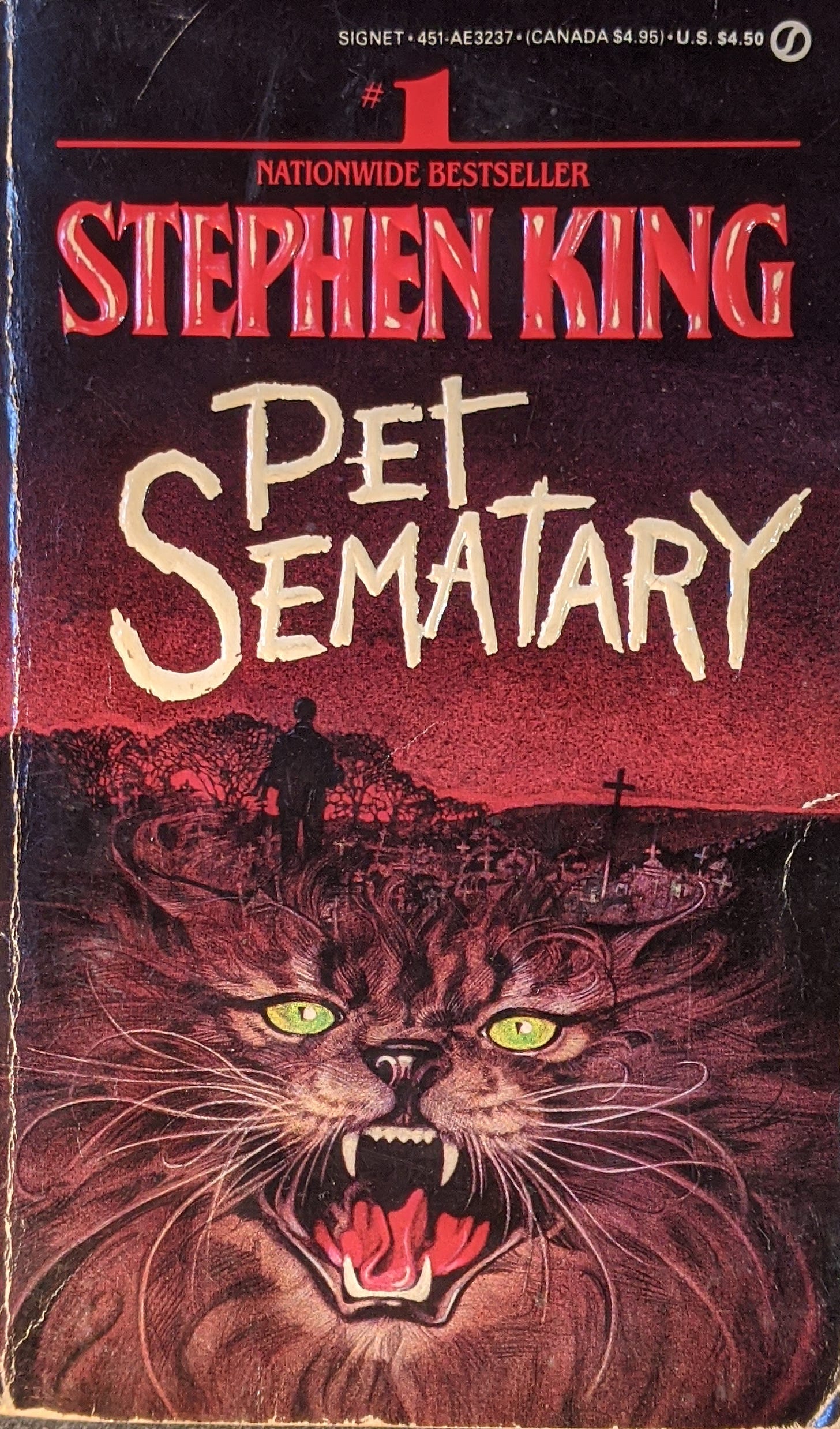

2 Pet Sematary (1983): Not only King’s scariest novel, but maybe the scariest novel ever written—high praise, even hyperbolic, but The Veil can’t come up with a better pick.4 King went for the gut with this one, killing off the Ideal Couple’s adorable son with a transport truck in the second act, a tragic accident that unhinges the family enough for one of them to attempt a Monkey’s Paw-style resurrection of the battered child corpse. One bad decision leads to another. The bodies pile up. There are no happy endings here, nor can there be.

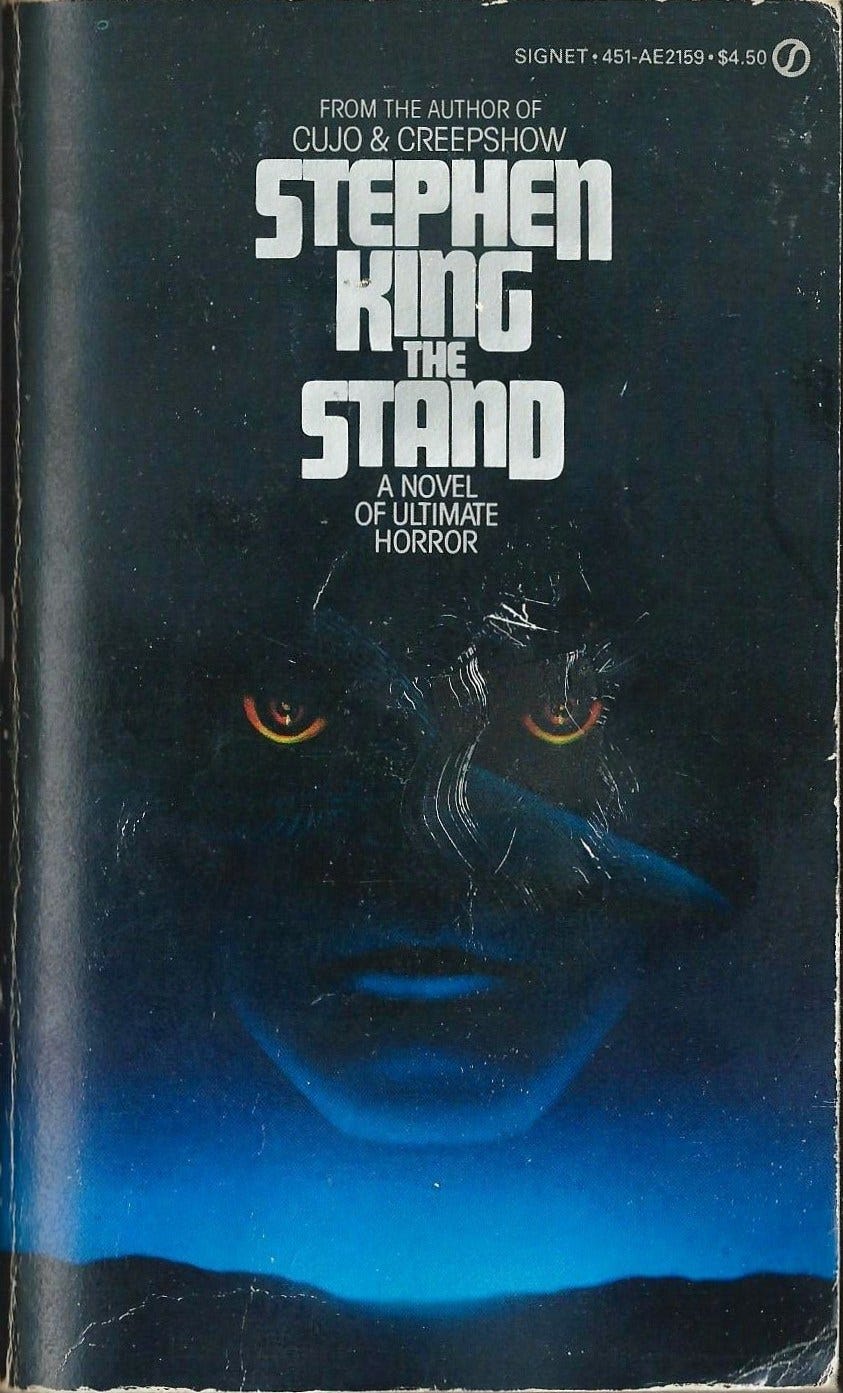

1 The Stand (1978): This sprawling tale of a deadly flu outbreak that precipitates a showdown between the forces of Good and Evil is so assured, so ambitious and damned readable, that its publication announced King as a special talent. The Stand has both the stony, stoic quality of an epic poem and the folksy good-heartedness of an updated Norman Rockwell painting.

(Runners Up: The Body, Mr Mercedes, Firestarter, Apt Pupil, Duma Key, Carrie.)

It may seem counterintuitive or even provocative for The Veil—whose editorial offices are located in the sleepy Canadian town that subbed for Derry, Maine, in the film adaptation—to slag It. The Veil is also not here to cast aspersions on the joy that millions of readers have taken from It, but returning the novel as an adult can be a very different and exhausting experience. It’s a long book, at least 300 pages too long, and the repetition and overstatement and the endless blocks of italicized or ALL CAPPED text may not seem as cool to the overextended, time-challenged adult reader as it did when that same reader had a whole summer to burn on a paperback. Then there’s the ending. Yikes. The only female character, a still pubescent victim of child abuse, offers her body up to the Losers Club for a life-affirming gang bang, followed by the naming of the archetypal evil monster as explicitly female while the boys scream “bitch” at her/it over and over. Is The Veil being too sensitive? Maybe.

Two of King’s best shorter works are outright homages to the Grand Poobahs of post-Victorian horror: H.P. Lovecraft and Arthur Machen. In “Crouch End,” two gormless American tourists stumble into a distinctly British suburb of the Lovecraft mythos, while “N,” named after a Machen story, reimagines a case of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder as a magical guardian protecting our world from the Apocalypse.

Unlike most classic horror fiction that preceded it, Salem’s Lot was as invested in the lives of its working-class characters as its gentry and denizens of the educated middle class.

The scariest horror tales are to be found in the short story and novella formats, but that’s an argument for another Friday.

Re. SALEM'S LOT: I've seen that PEYTON PLACE + DRACULA comparison a few times over the years. Any idea who said it, and where/when? Given that the TV scriptwriter for Hooper's version was the creator of PEYTON PLACE, I can't help but wonder if >>that<< led to the comparison. Or, does the comparison pre-date his hiring and is it in fact the reason he was hired?