The Veil Top Ten: Scary Novels Edition

Finally, a Best Horror Novels list that doesn't contain The Silence of the Lambs

The task of trying to define “the novel” is so daunting that The Veil editorial team was tempted to quote the Miriam Webster dictionary definition, a gambit, we’re told, still in vogue with high school and undergraduate essayists. But if the novel is more than just a padded-out short story, a few words about definition are in order.

The great Flannery O’Connor wrote in an essay that a short story consists of a “single dramatic action.” The novel could then be defined as a series of dramatic actions culminating in a satisfying finale. So what can a horror novel do with all those extra dramatic beats and sheer length? From The Veil’s point of view, the horror novel excels in the potential for characterization. Whether the novelist is commenting directly on a character’s motivations, experiences and reflections, or revealing character through a variety of dramatic situations, the resulting intimacy between reader and fictional character can’t be matched by the short story form (not to the same degree). The best novelists know how to manipulate that intimacy to amplify the emotional effects horror fans love, whether it’s the slow build of suspense and dread or the feelings of pathos, horror and pity evoked by the monster.

The novel’s length (40,000+ words) also allows for a fuller exploration of themes and ideas, while the proliferation of subplots and supporting characters can immerse readers in what feels like a fully realized world. That combination of rich characterization and world-building make even the most overtly supernatural novel more believable and therefore more frightening.1 (Note: the novels are not grouped in any order of merit.)

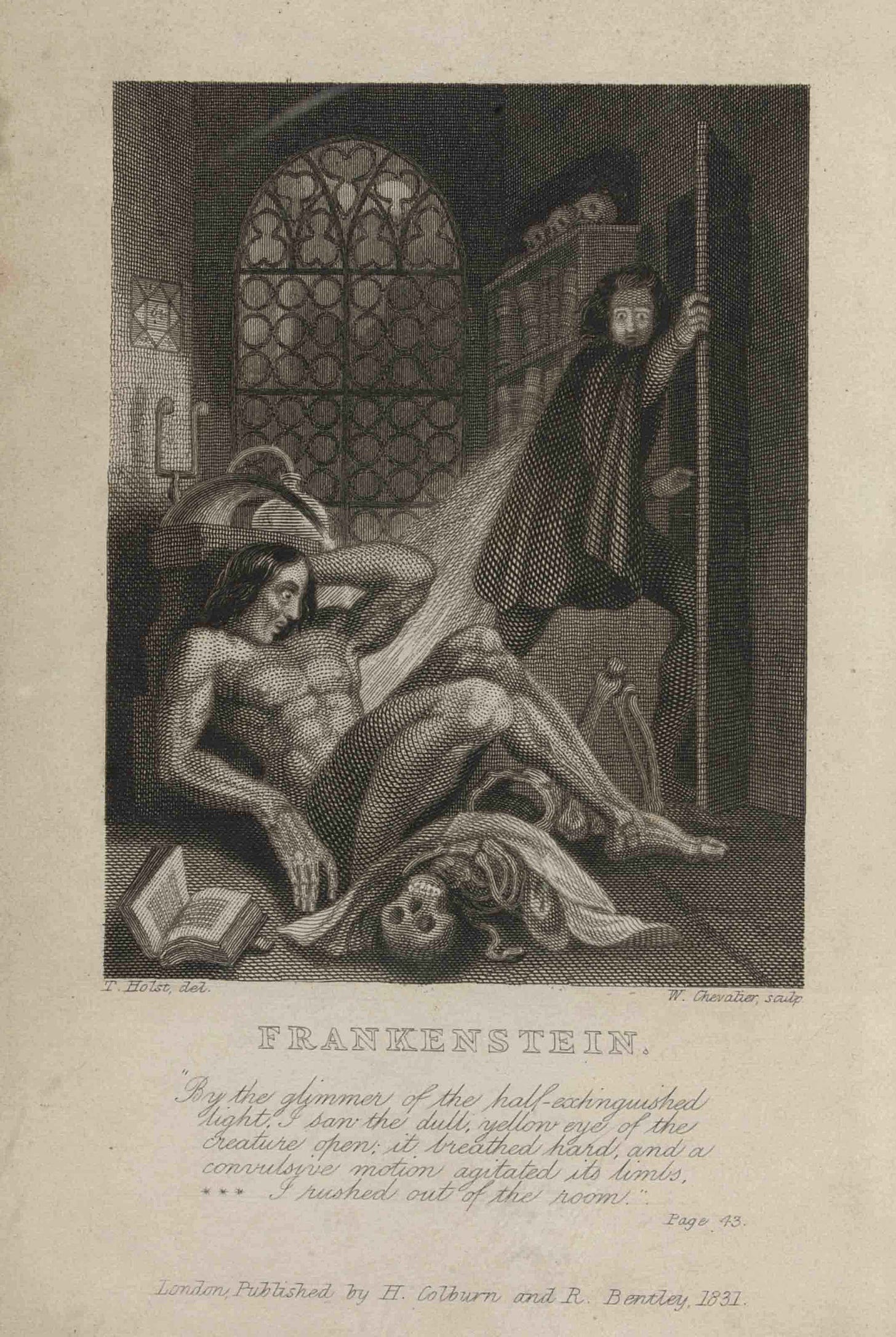

Rosemary’s Baby, Ira Levin: If Rosemary’s Baby had a different ending—if, say, Rosemary was suffering from pregnancy-induced mental illness, as her doctor suggests—would it still be a horror novel? Ira Levin was a master of the tightly paced thriller who certainly could have pulled off a daring act of misdirection. Luckily, Levin sensed the potential in going full-Satan, a decision that gifted readers with the novel’s final scene, a set-piece of shocking, gruesome comedy only possible in the horror genre.

The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson: It’s a good idea to reread Jackson’s classic haunted house novel every few years to remind yourself that it deserves all the hype it’s received since its 1959 publication. No amount of rereading dulls the novel’s atmosphere of disorienting oddness, an effect achieved by Jackson’s labyrinthine prose, which mimics the sing-song inner monologues of a sensitive, thoughtful but utterly mad spinster. The brutal ending, which puts the therapeutic finale of Mike Flanagan’s Netflix adaptation to shame, also retains its power to shock, disorient and satisfy.

Pet Sematary, Stephen King: What would a Stephen King novel look like if he dared to put his protagonists fully, completely through the meat grinder? The correct answer: Pet Sematary, still the scariest and unnerving entry in the King canon.2 Whether intentionally or not, Pet Sematary mimics the structure of classical tragedy. The protagonist, Louis Creed is one of us, only a little smarter, a little more successful, more thoughtful. When Louis is tripped up by a forgivable character flaw—an inability to look death in the face—the ensuing punishment is grossly out of proportion to his crime. As his punishment unfolds, we shudder at his undoing. We lament his undeserved fate. And we become more fully human.

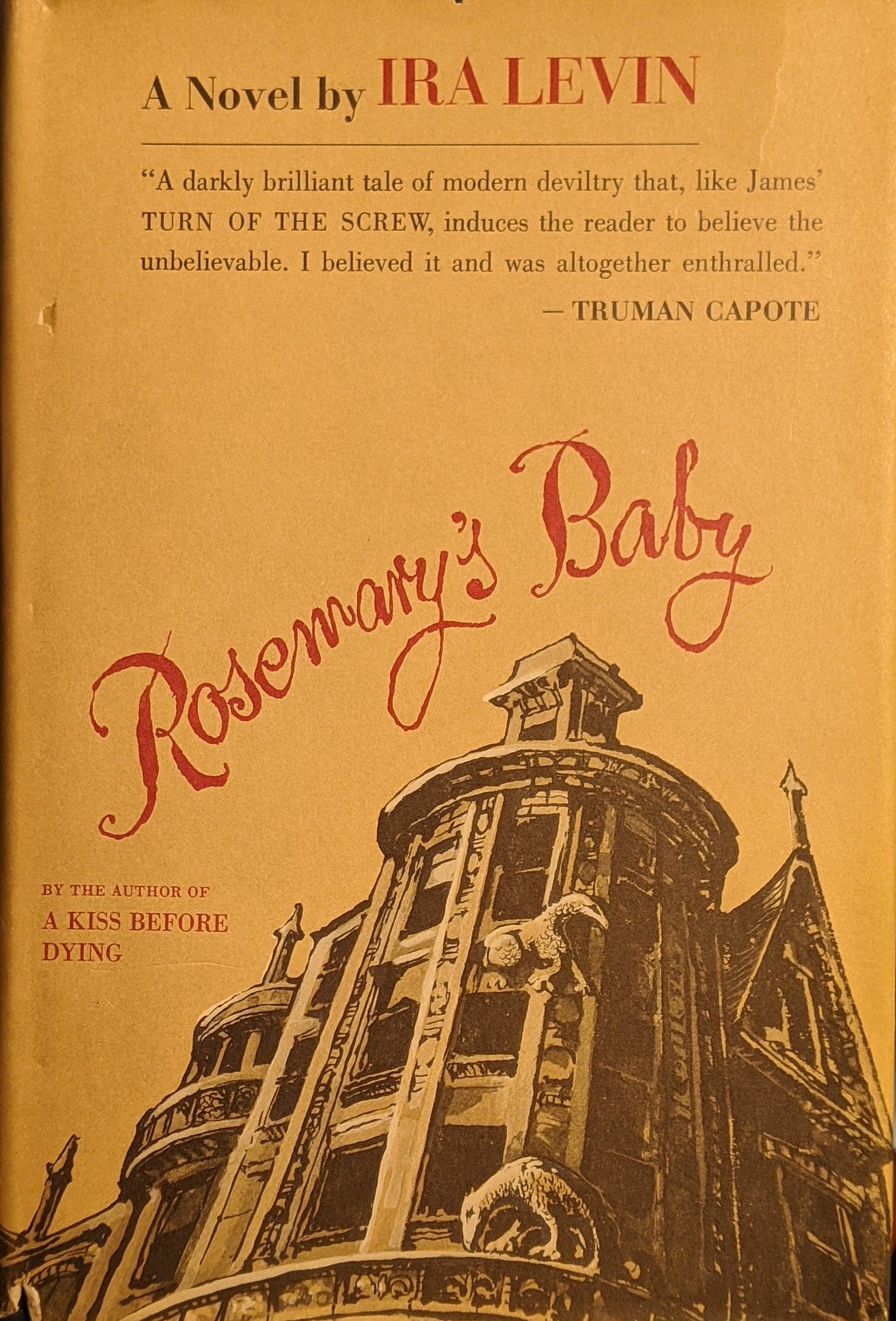

Burnt Offerings, Robert Marasco: Is Burnt Offerings the best haunted house novel ever written? Yes and no. Though it lacks the thematic sophistication and character depth of The Haunting of Hill House, no other novel so fully realizes the metaphorical potential of the house as a symbol of the disordered familial psyche.3 Hill House is all whispers and promises and veiled threats; the Allardyce House of Burnt Offerings is a devouring mother whose not afraid to show her teeth when threatened. Pick your poison.

The House Next Door, Anne Rivers Siddons: Another contender for Best Haunted House Novel, Anne Rivers Siddons single foray into the genre uses the powers of suggestion and misdirection to locate the reader at a seemingly safe distance from a malicious haunting that destroys several lives. As the bland title states, the novel’s narrator lives next door to the haunted house and only witnesses the horror second-hand. Until she doesn’t. Evil spirits apparently don’t obey property lines, even in the narrator’s idyllic upscale neighbourhood, a realization that comes too late.

The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty: No other horror novel takes the notion of evil as seriously as The Exorcist. William Peter Blatty, a devout Catholic, applied his intimate knowledge of theology to the task of defamiliarizing our preconceptions about the Devil. His demon is not the tragic Lucifer of Milton or The Rolling Stones but a lethally pathetic parasite feeding on human innocence and love, an aborted angel roiling in fecal muck. That Blatty still gives his demon all the best lines attests to his novelist’s instincts.

Incarnate, Ramsey Campbell: Nobody reads a Ramsey Campbell novel for the plot and characters. Not that Campbell, one of the masters of contemporary horror fiction, can’t tell a story or create a believable character, but his unmatched gift is for atmosphere—no author since Lovecraft so consistently locks reader inside a prison of mood and tone like Campbell. In Incarnate, the survivors of a sleep experiment are reunited years later when their shared dreams and nightmares begin to incarnate in the real world. The novel eerily mimics the processes of drifting in and out of a state of half-sleep, the lulling dissolution into dream and bodily paralysis, the scramble for purchase in the physical world after the sudden waking. Campbell puts us through these familiar rhythms, ratcheting up the nightmares each time, until, like a deranged caregiver, he pulls the pillow out from under our heads and suffocates us. Great stuff!

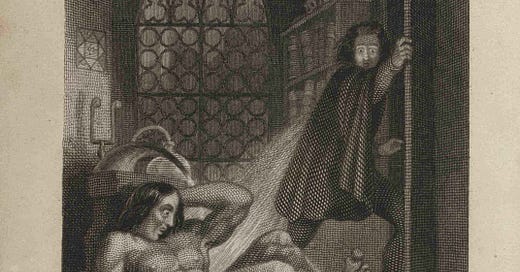

Frankenstein, Mary Shelley: Mary Shelley’s visionary novel argues that the truly venal sins are committed in service to our better natures. Victor Frankenstein is a brilliant idealist whose studies of chemistry and medicine unlock the secret of regenerating dead matter, a discovery that takes Victor beyond the boundaries of natural law. What he brings back from that forbidden territory so horrifies Victor that he disowns his experiment and tries to hide behind the veil of domestic respectability. But natural law, even when violated by the best of intentions, is merciless.

Fever Dream, Samanta Schweblin: A woman lies in a hospital bed, likely blinded by a chemical leak, her only companion a mysterious seven-year-old boy who, we learn later, is possibly the vessel of another boy who recently died. The need to qualify the above plot points with so many adverbs attests to the surrealistic power of Samanta Schweblin’s unclassifiable Fever Dream, a long novella told in dialogue form that reads like a transcribed nightmare.

Starve Acre, Andrew Michael Hurley: Starve Acre may or may not be the best of Andrew Michael Hurley’s stunning trilogy of folk horror novels but it is the most overtly frightening, at least to The Veil’s tastes. Set in the early 1970s in the remote Yorkshire Dales, the short novel intrudes upon a couple grieving the death of their only child. The husband, a typically cerebral academic, becomes obsessed first with the history of a massive tree that once grew on their property and served as the local gallows, then with the skeleton of a hare he finds on his searches for the ancient tree’s roots. The wife turns to the occult to assuage her grief. Neither of the grieving parents senses the subterranean forces they are summoning with their misguided explorations. Some things are best left buried.

Runners Up (or numbers 11-20 on a future The Veil’s Top Twenty Horror Novels list): Apartment 16, Adam Nevill; Let the Right One in, John Ajvide Lindqvist; The Only Good Indians, Stephen Graham Jones; I Am Legend, Richard Matheson; Harvest Home, Thomas Tryon; The Stand, Stephen King; Dracula, Bram Stoker; The Edge of Running Water, William Sloane; The Ceremonies, T.E.D. Klein; You Should Have Left, Daniel Kehlmann.

This probably explains the absence of the longer works of HP Lovecraft, William Hope Hodgson, Algernon Blackwood, and Edgar Allen Poe, none of whom excelled at character depiction.

The Veil will also accept Revival as an answer, which is why it and Pet Sematary both made our Top Ten Stephen King Novels list.

Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” remains the source text for the modern haunted-house novel, though it’s only about 7,000 words.

And now I have even more books to add to my TBR list. Thanks for sharing the list!

Finally getting around to reading this list! I love watching certain kinds of horror movies; I get that craving everyone once in a while. I was thinking about horror books the other day and that I've mostly read Stephen King. He has been the basis of my horror book experiences. I'm excited to try some of these horror books and figure out what else I like.